For eight hours a day (ish), I am a teacher, and so I find myself implicated in an ongoing struggle for direction. It is assumed, and schools and parents do a lot of that (assuming), that there must always be a place one should be going to, and this destination needs to be worthy in its own right, and must be achievable by a set of clearly delineated, but suitably challenging to achieve, steps. If you can point to that destination and spell out all the steps, you’ve got direction. But what if you don’t?

Isabel is a recent anthropology graduate who finds herself in a time and space that is both after and before. She is post-graduation, but back in her hometown. She left only to return, and now has to figure out if, how and why she might wish to leave again. She’s got three months, while she is house-sitting for some family friends. But then she takes a job as a receptionist at a yoga studio, which brings with it the simple realisation that ‘Oh well – so college didn’t matter. I would be a person in a chair’. As the novel progresses, however, it turns out that maybe Isabel is not so lacking in purpose at all. Eli is the son of the couple for whom Isabel is house-sitting. He’s also – it is later revealed – one of ‘the ultimate boys’ of Isabel’s high school years, and someone with whom Isabel feels there is unfinished business.

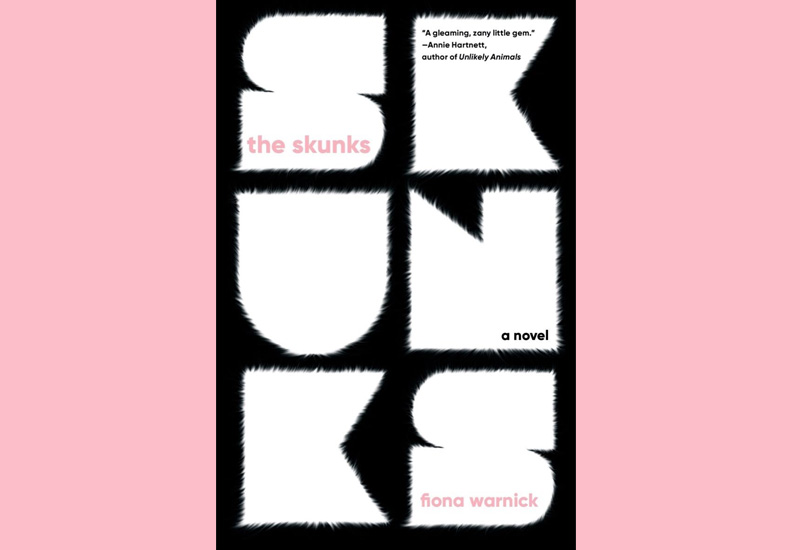

So what about the skunks? Don’t think this is like a book I recently reviewed in which there was a central, and titular, animal that was not as important to the book as it should have been. The skunks are key. Indeed, Isabel’s whole existential struggle is summed up by the grammatical paradox of one of the first lines introducing the animals: ‘There were three skunks, and they walk perpetually across the lawn’. Past becomes present, and the skunks permeate the book with interpolated sections in which we see the skunks, with particular emphasis on the eldest skunk, muse on the nature of the world and their place in it (with help from a wise oriole), and venture from home only to realise where they are meant to be all along.

It is tempting to call this a coming-of-age novel. But I’m not sure it is. The oriole, we are told, ‘wanted to understand the world so he could care for it more accurately’. This novel is an exercise in trying to understand, without insisting on revelation. It has the tenderness of a child’s question, without the finality of an adult’s narrow response. And that makes Warnick’s debut something special.

Click here to change your cookie preferences