Turkey has been intensifying its promotion of a “two-state” solution in Cyprus, turning it into the centrepiece of its diplomatic narrative – or so it appears.

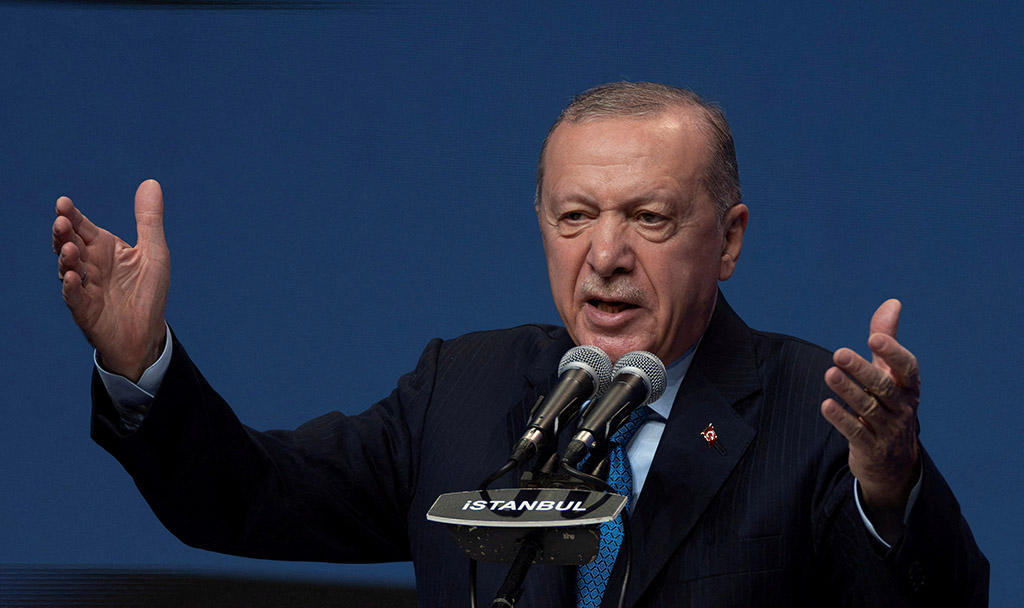

Most recently, during a meeting in Ankara with the Cypriot Turkish leader Tufan Erhurman, President Erdogan called the two-state model “the most realistic” option.

Ankara presents the forced division of Cyprus not as the political and legal aberration that resulted from its 1974 invasion of choice, but as the basis for a “realistic” and permanent settlement.

Yet for all the bold declarations, an authentic two-state outcome is not what Ankara truly seeks. Such a scenario undermines its long-term strategy. Its oft-repeated declarations may appear unequivocal. Over the decades, Turkey has entrenched its military, economic, religious, cultural and demographic stranglehold in the territory of the Republic of Cyprus (RoC) it has occupied since 1974.

It has stationed tens of thousands of Nato-armed and trained troops, constructed infrastructure and military bases to project power across the region and transferred over 200,000 Turkish settlers – a war crime under international law – with the intent to alter the demographic character of Cypriot society. It has systematically erased or desecrated the cultural and religious heritage of Cyprus. These facts on the ground appear consistent with Ankara’s stated objective of formal partition.

“Even if there were no Muslim Turks in Cyprus,” wrote former Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu in his seminal book Strategic Depth: Turkey’s International Position, “Turkey is obliged to maintain a Cyprus question. No country can remain indifferent to such an island, located in the heart of its own vital space.”

The phrase “vital space” should send a chill down the spine of any European familiar with the Nazi vocabulary of Lebensraum.

By referring merely to “Muslim Turks”, Davutoglu reduces the Cypriot Turkish community to a religious identity – erasing their distinct political, social and historical agency as Cypriots.

His phrase that “Turkey is obliged to maintain a Cyprus question” implies it must be perpetuated until Ankara secures its desired outcome – precisely what Turkey has pursued for decades.

But, Cyprus is not merely “an island”. The RoC is a state of long standing – sovereign, internationally recognised, and a member of regional and global organisations.

Crucially, this strategic outlook on Cyprus is neither new nor unique to Davutoglu. It reflects a diachronic doctrine that has long shaped Ankara’s posture – across secular, Islamist, military and elected governments. Its implementation has been consistent. To paraphrase Clausewitz: diplomacy, politics, hard power, demographic engineering and – some might argue – bullying have become the continuation of war against Cyprus by other means.

In the fall of 1974, the late Lord Caradon (formerly Sir Hugh Foot, the last British governor of Cyprus) presciently defined Turkey’s strategic goal. He stated in the House of Lords that what the Turks wanted was to be “masters in the north and partners in the south”. Caradon’s maxim captures the essence of Ankara’s policy against Cyprus.

Turkey does not seek two equal, sovereign and independent states in Cyprus. It seeks co-sovereignty over the entire state – political, military, economic and diplomatic. Its aim is to prevent either side from acting autonomously in a region Ankara regards as part of its “vital space” – one it increasingly views through the lens of Blue Homeland (Mavi Vatan), encirclement (kuşatma teorisi), and broader neo-Ottoman ambition, fuelling revisionist and irredentist moves aimed at strategic control.

The problem for Turkey is not partition – it’s independence. Not two states, but two satrapies.

This objective has a long pedigree. In 1974, Turkey tried to enforce it through war. It failed – and has been pursuing it ever since, through other means.

Ankara’s calculus in Cyprus is shaped by broader regional imperatives. The Cyprus question must be understood within the context of Eastern Mediterranean power politics. The region remains a theatre of intense geopolitical competition. Sustaining its occupation – and securing post-settlement control – bolsters Turkey’s posture vis-à-vis the United States, the United Kingdom, Egypt and Israel – all of which maintain enduring equities in the region, from Nato basing to energy corridors, intelligence cooperation and maritime security. A firmly EU-aligned Cypriot state threatens to disrupt that calculus.

There is also a diplomatic layer to this calculus. Ankara is fully aware that a two-state formula is a non-starter in international law. So why promote the two-state narrative?

Most likely, it is a tactical gambit. By advocating an extreme position, Ankara seeks to shift the negotiating process toward a confederal structure that grants Cypriot Turks sovereign equality – or, failing that, to use the deadlock to consolidate de facto control in the occupied areas without incurring the political cost of formal annexation.

Confederations, by definition, are composed of two sovereign entities. Even a “loose” federation – pressed through under external pressure – could serve Ankara’s long-term goals.

Domestically, the two-state narrative resonates with nationalist sentiment, reinforcing the political standing of President Erdogan while diverting attention from economic turmoil and democratic backsliding.

In practice, the two-state formula offers Ankara the benefit of strategic ambiguity. It allows Turkey to manage expectations, justify the status quo, and cast the Cypriot Greek side as “unrealistic”. Yet beneath the rhetoric, there exists only one roadmap: that of a Turkish “peace”.

Even with the recent selection of Tufan Erhurman as Cypriot Turkish leader – a figure long associated with pro-solution politics – there is little indication of a substantive shift in the approach of Ankara. On all key major strategy and policy decisions, the decisive hand remains that of Ankara.

The RoC is, de jure, one island – one internationally recognised state and government under international law, member of the EU. It encompasses the entire territory of Cyprus, with the sole exception of the two British bases. Its people constitute a single political community, inclusive of all Cypriots, whether of Greek, Turkish, Maronite, Armenian, or Latin ethnic background.

What Turkey proposes defies international legality – and denies the pluralistic, lived identity of Cyprus itself. What it seeks is not peaceful coexistence, but post hoc legitimisation of a military fait accompli.

A settlement cannot be built on imposed division, demographic engineering or coercive diplomacy. It must rest on international law, the EU acquis, and the principles of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law – including the free and equal participation of all Cypriots in a shared political future and in a common homeland.

Cyprus cannot be reconstituted through enforced separation or permanent inequality. A viable peace cannot emerge from segregation. Attempts to institutionalise ethnic division edge disturbingly close to apartheid.

In the end, the two-state rhetoric may be less a blueprint for peace than a smokescreen for permanent control. Behind the slogans lies a strategy of prolonged dominance, not reconciliation. But history is not deterministic or written in stone. The recent Christodoulides–Erhurman meeting offers a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel – let us hope it is not the oncoming train. What is needed now is clarity, consistency, and courage – from Cypriots, from the UN and EU, and from the broader international community.

Cyprus remains a test – of law over force, of rights over might, of diplomacy over diktat. The outcome will echo far beyond its shores. It will either vindicate the rules-based international order – or reveal the cost of failing to defend it. Our motto as Cypriots: #CyprusWholeAndFree.

Euripides L. Evriviades is Ambassador (Ad Honorem) and senior fellow at the Cyprus Centre for European and International Affairs, University of Nicosia.

Click here to change your cookie preferences