In the specialist in turning out warming soups in the north THEO PANAYIDES meets a former mechanical engineer who has moved into the late night dining scene. He now lives for reading books and talking politics

Every cloud has a silver lining – and the one small upside of Covid restrictions is the way they’ve encouraged more Greek Cypriots to explore the foodie scene in the occupied north, which is less hung up on SafePasses and vaccination status. Heybe Corba (pronounced ‘chorba’), a 15-minute walk from the Ledra Street checkpoint in Nicosia, has become something of a meeting point, according to its manager Djamal Tarazi. “Every night, almost, I have one or two [Greek Cypriot] friends coming here,” he tells me in fluent if imperfect English. “And these people that come here, they are all well-educated.”

His customers’ level of education isn’t usually a concern – but Djamal appreciates the informed conversation from the ‘other side’; he likes to talk, especially (though by no means exclusively) about the Cyprus problem. “There are too many books written about the Cyprus issue,” he says, using ‘too many’ – in the Middle Eastern way – to mean ‘very many’. “I really like them. I’ve studied most of them.” He’s currently reading The Communist Party in Cyprus by Yiannos Katsourides, with a book on Makarios coming up next. He usually sets aside a couple of hours a day to read books, which isn’t necessarily what you’d expect from the manager of a 24-hour soup place.

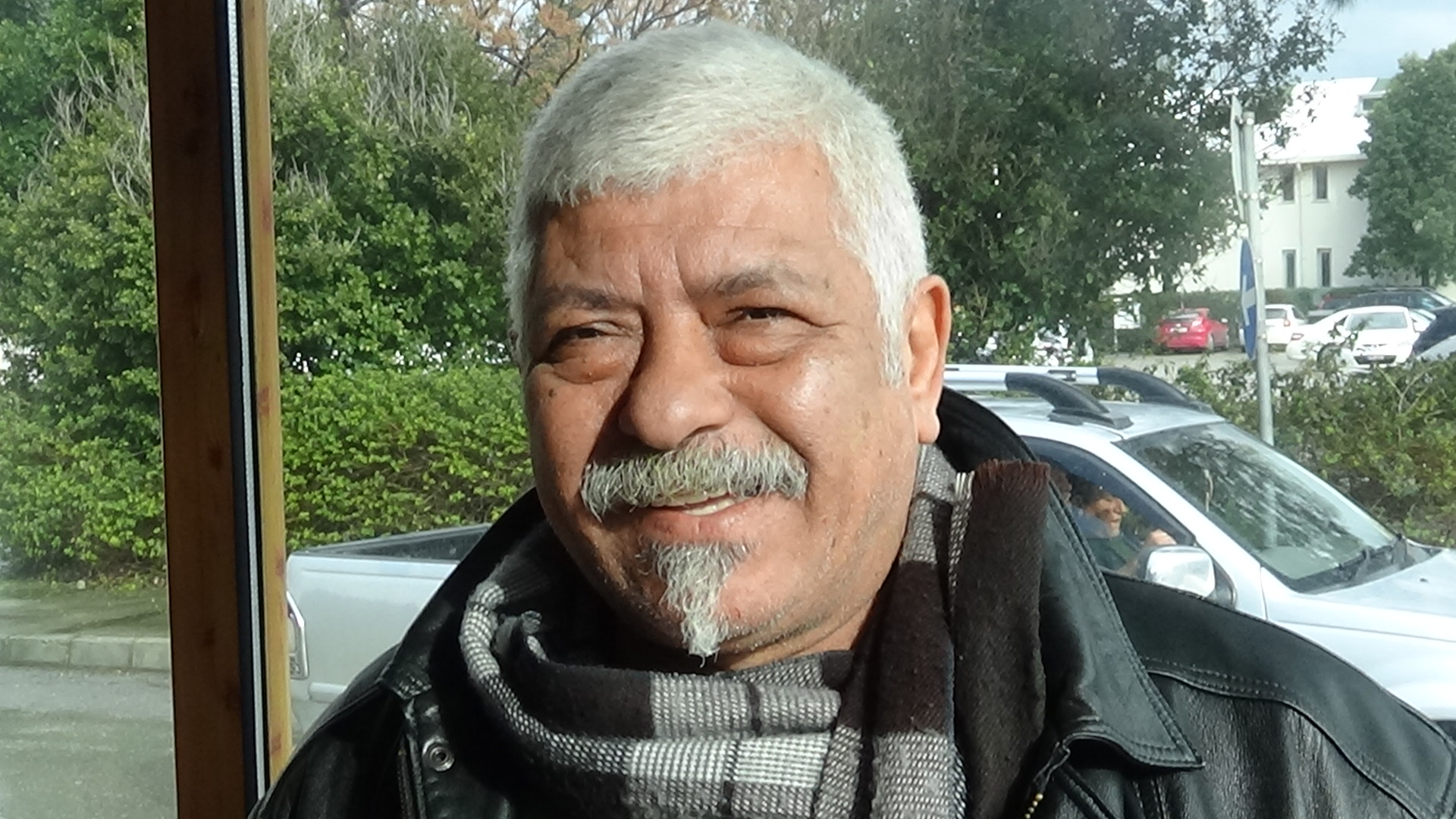

He’s 62, a Leftist and an atheist, with a white goatee and eyes so puffy they tend to narrow into slits whenever he laughs out loud (which is often). He’s a little late, and looks a little haggard when he finally arrives; I take out my tape recorder – but he says he’d like to have a coffee and smoke a cigarette first, “because I just woke up”. It’s 1pm, the place filling up with the lunch crowd, but Djamal’s day is just kicking off: “I worked until five o’clock,” he explains. “I’m here from six or seven in the night, until five in the morning. Every day”. Lunchtime is actually a strange little outcrop in his routine, the equivalent of someone waking up at three in the morning and wandering about for a couple of hours: Djamal always has a siesta, so he’s going back home in a while to get some more sleep. It’s a rather eccentric way of life, not to mention tiring – but he’s used to hard work, he assures me, and never gets tired. “I never lose my energy. I still feel like I’m in my 40s.”

We sit outside, on the restaurant’s covered patio – clearly designed for summer nights, and deserted on this wintry Friday lunchtime (the inside, on the other hand, is bustling). A stray dog wanders forlornly. It’s cold and wet, with rain rattling down and cars roaring by a little distance away. Heybe Corba’s location is a little charmless, on a busy main road wedged between various warehouses and supermarkets (it’s actually the stretch where the railroad tracks used to run, back in the day) – but the avenue comes in handy for parking, he tells me, and it’s not so busy at night when the place gets full anyway. This is not a restaurant for haute cuisine; it’s a late-night and early-morning place where people come “to carry on the conversation” from earlier establishments – and of course to greet Djamal himself, who’s been running it for the past seven years.

The clientele are a mixed bag: people who start work very early – “like bakers, and municipal workers” – and come to breakfast on a hot bowl of soup before heading off, high-school kids who appreciate the casual vibe (“I don’t put any pressure on them,” explains Djamal), late-night wanderers winding down from nearby bars and clubs. Is there ever any trouble, in the wee hours? “Sometimes,” he replies. “We’re talking about nightclubs. People come from nightclubs, they are full of alcohol, they don’t know what they’re doing. So sometimes we have – very few – fights.” He’ll let people argue, then “if I see it’s getting heavier, I telephone to police” (they’re just down the road). “And a couple of times I’ve gone outside and argued with them… And I always say to them: ‘I’ve lived in mountains, I don’t care. You want a fight? I’ll fight!’. So they respect me”.

The ‘mountains’ in question are the town of Lefka, where he grew up. Djamal’s dad was a truck driver working for the mining company (Skouriotissa, just outside Lefka, was the biggest copper mine on the island) – which sounds pretty hardscrabble but in fact he made an excellent salary and Djamal, the oldest of four, went to London to study mechanical engineering. Heybe Corba wasn’t always his life, not by any means. For years he ran his own business, as a food wholesaler. For many years (24, in fact) he was married, living a conventional family life (he has two kids, a son and a daughter, both now in Britain). He and his ex-wife separated about eight years ago, “that’s why I started here,” he adds rather ruefully (his business had already started to founder, rocked by the crisis). Lots of big changes in his life, I point out. Does he regret the way things turned out?

“Actually…” nods Djamal – and it takes me a moment to discern that he means ‘Actually, yes’. “Because you had a proper life,” he sighs, switching abruptly to the second person – “and now you are single, you don’t care nothing. No-one is waiting for you at home – so you don’t care to go home or not to go”. It occurs to me that, even beyond chatting to Greek Cypriots and his literary friends (they all read books, “and they come here, and we criticise the books”), there’s a deeper reason why he doesn’t mind coming to the shop every day: to stave off loneliness.

Why not find someone new? He must meet lots of people, in this business.

The two hours a day for reading books are non-negotiable. Then there’s the fact that “I love going around, in the mountains. Like this weather,” he adds, gesturing vaguely at the pouring rain, “I always dream to go with a tent on the mountain, open my tent, light my fire, make my kebab while it’s raining. And I want to get wet! So I want a woman to accept this. In the winter, I want to go to the seaside and swim. I like it,” he adds, chuckling at my startled expression. “Or, I like dancing. It’s difficult with this age, over 60 – she’ll say ‘Oh I’m 60, I’m gonna dance?’. For me, age is just a matter of mathematics”. He’s annoyed when younger customers, trying to be respectful, call him ‘Uncle’ or ‘Dad’; it vexes the life force that still swirls around in his blood. “I never think of my age. And I don’t act like my age.”

Clearly, Djamal Tarazi isn’t your typical Turkish Cypriot – but he’s still a Turkish Cypriot, which at once makes him interesting. It’s not just the restaurant scene one explores by crossing the checkpoint – it’s also the glimpse of a worldview that’s both identical and subtly different. “These communities, they’ve been living together now for 600 years. So the culture is the same,” says Djamal, speaking of the two sides of the Green Line (religion is the main divisive force, he adds, pointing the finger at the Orthodox Church; he himself, of course, isn’t much of a Muslim) – yet it’s still mildly shocking, to a Greek Cypriot, to hear someone talk of the “operation” in 1974 instead of the invasion. His politics don’t always satisfy, despite all the books he’s read, as when he insists that the July 15 coup was the only reason for the ‘operation’. “I mean, Turkey was happy where it was. Suddenly it found itself in Cyprus – but why? If you didn’t have the coup, if you didn’t abolish the Republic of Cyprus and try to kill the president of Cyprus, Makarios, Turkey would never have come to Cyprus”. I don’t bother asking why, in that case, they’re still here.

Still, his experience is full of vivid details. Childhood in Lefka, an initially mixed town that became Turkish Cypriot (but surrounded by Greeks) due to intercommunal violence, and the fraught, free-floating tension of the mid-60s: Djamal’s father worked with Greeks in the mining company, his grandma would take him down to Xeros to visit their old (Greek) neighbours – but he also recalls going to the seaside as a family, and “even though the sea was very close to Lefka, we were frightened to go because it was all Greek people there… Not that they were going to do anything to us,” he adds – but that was the point, you never knew. (They went 10 miles down the coast to Limnitis instead.) He recalls 2004, the deep Turkish Cypriot distress after the rejection of the Annan Plan – he was even more distressed, as a man of the Left, that Akel had refused to support it – and 2017, the ultimate failure at Crans-Montana, after which “everything changed in Turkey”.

All that said, he remains optimistic that a federal, bicommunal Cyprus will someday emerge, waving his cigarette disdainfully when I mention Erdogan’s current obsession with two states. “I don’t care about that. I’m Cypriot – he’s not Cypriot. He’s just playing a game.” Politicians play games in general – but time moves on, things change regardless. “People don’t care anymore,” says Djamal sharply. “They don’t care… I know a [Greek Cypriot] guy, he went to Yialousa. He said ‘I’m not waiting, you bastards, to solve the problem! I’m going to my land’.” He shrugs, with the authority that comes of countless conversations with random strangers at unsociable hours: “People are fed up”.

Djamal, too, is starting to flag a little; it’s not that he’s tired – but he needs that second cup of coffee, it’s part of his process. I’m a bit restless myself, getting cold and thinking longingly of hot bowls of soup. We decide to go inside, and I gaze around the place that’s become his second home in the past seven years – the locus of his second life, a life that appeared in middle age, a life of holding court, greeting strangers, wading through the murk of the Cyprus problem, staying up when the rest of the world has gone to bed. The two-in-one chicken and lentil soup is superb, and I wash it down with a small ayran – then say goodbye and gingerly step around puddles, all the way to the checkpoint.

Click here to change your cookie preferences