Since he was a teen, Andreas Andreou has been obsessed with the long-empty Berengaria hotel, but he has good things to say about its renovation

Andreas Andreou is quite young – he turns 34 this month – but he’s already been on TV several times, plus radio and print media: CyBC, Sigma, 24 Ores on Alpha, interviews with ‘K’ and Parathyro (the Sunday supplements of Kathimerini and Politis, respectively), even Eleftheria in the UK.

What’s strange, however, is that almost all of these media appearances have to do with something that took place when he was even younger – namely, Berengaria: Hotel of the Kings, a 364-page book he published (in Greek) at the very tender age of 19.

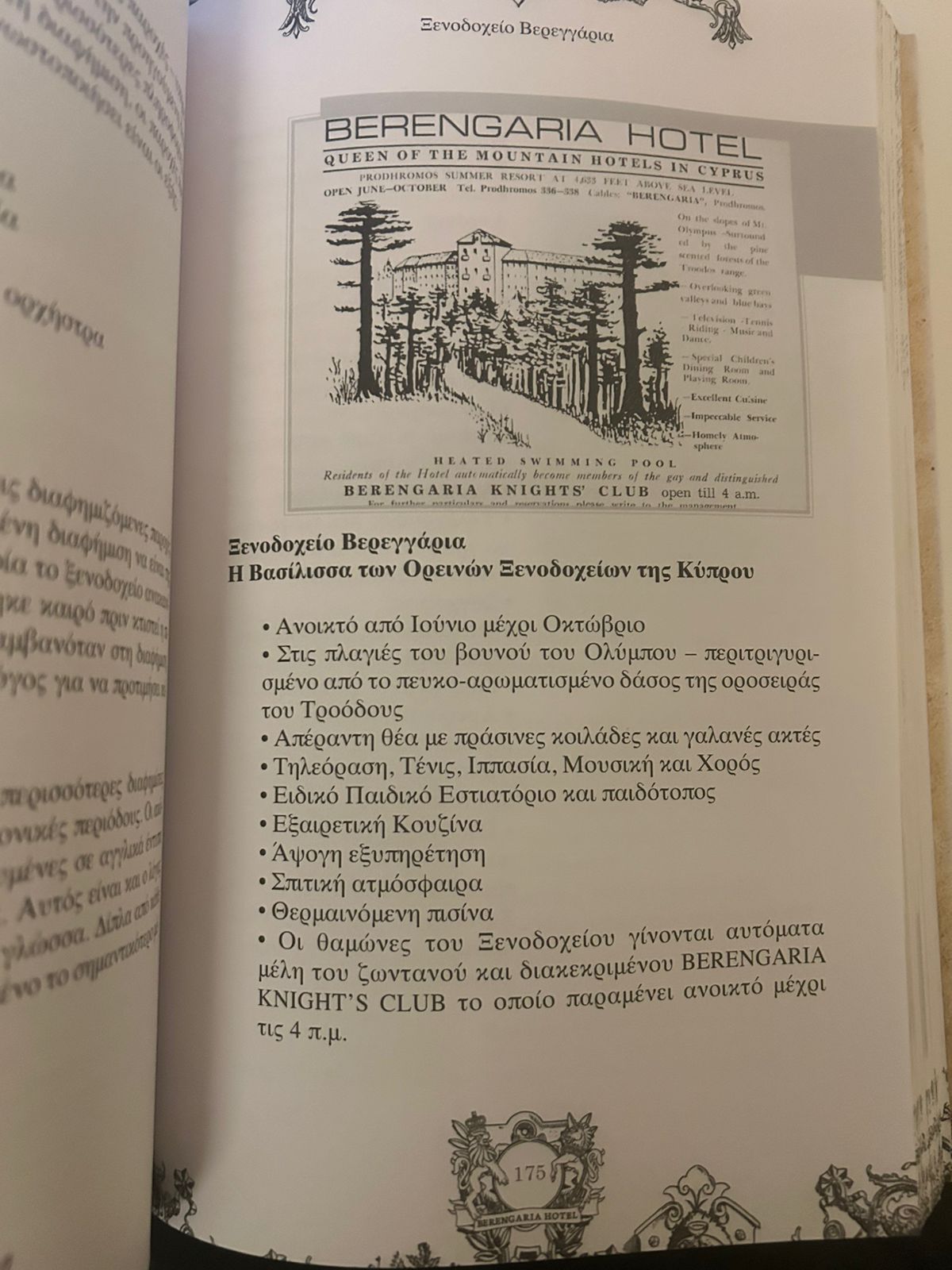

Everybody knows the Berengaria, a grand hotel, overlooking the mountain village of Prodromos, that played host to distinguished visitors – from Winston Churchill to King Farouk of Egypt – for 53 years. It opened in 1931, closed in 1984, and has spent the past four decades as a decaying husk, “a symbol of the glory and decline of another Cyprus,” as Andreas told Parathyro (“A fairytale Cyprus with a palatial hotel, known even to princes”), as well as a constant source of legends and spooky stories.

‘The Haunting History Behind Cyprus’s Berengaria Hotel’ is the headline of a 2018 article at Culture Trip, an American travel website. The hotel – which is now being rebuilt and renovated, due to re-open fully in a couple of years – has become our local version of the Overlook in The Shining, the tales of mysterious goings-on adding to its lustre.

“According to the legend, all three brothers died mysteriously and under suspicious circumstances,” claims the Culture Trip piece, referring to the three sons of Mr Kokkalos, the original owner. “Additionally, another story holds that two female ghosts roam the hotel. One of them was found dead in the swimming pool, and it’s said she still hangs around in an effort to avenge her death…”

It’s not that he wasn’t mildly thrilled by such tall tales, recalls Andreas, thinking back to his adolescent research. “The talk was that someone had died here, or that they all left suddenly because something happened… Or that, when you go, your car engine switches off by itself – which OK, for a 17-year-old was a bit intriguing.

“But something inside me was saying that there’s something else here… I felt an incredible calling, and I felt there’s a story here – beyond all that nonsense about ghosts.”

Looking back, there was no obvious reason why a random teen should’ve done such voluminous research – and eventually written a book – on the Berengaria. The hotel wasn’t on the official tourist map, various previous attempts to revive it having come to naught; Andreas recalls a bureaucrat at the Cyprus Tourist Organisation being unable to comprehend – she said so several times – why anyone, let alone a kid, would be interested in that pile of bricks. He wasn’t even from Prodromos – though his mum’s people hailed from nearby Pedoulas and he was admittedly from a village, a tiny hamlet in the Solea area.

He’d seen the hotel as a child (mostly from a distance, its sloping roof glimpsed through a canopy of trees), and also recalls being profoundly affected, at seven years old, by the “haunting beauty” of Marina Maleni in a CyBC show filmed at the Berengaria. Growing up, though, it didn’t feature much in his life – and besides, he had bigger problems.

Looking back, the tail-end of his teens – a few crucial months in 2010-11 – marked a culmination for Andreas Andreou, a special time in his life. In December 2010, at the end of his first term at uni (European Studies with Politics at the University of Essex, transferring to Humanities in his second year), Berengaria was published, going on to sell over 2,000 copies and attract instant media attention.

A few months later, in 2011, Accept – LGBT Cyprus was approved as an NGO, allowing activists to talk publicly about being gay, and sexual orientation in general – all of which played a decisive role (combined with falling in love “for the first time, consciously, with a man who’d been flirting with me”) in his own coming-out around the same time.

We sip coffee (iced latte for him) at Halara in old Nicosia, on one of his regular jaunts down from Troodos where he’s lived for the past few years. We’d planned to meet at another café – and in fact we did meet there, but he felt the music would intrude on the interview and suggested we move. He has some experience in journalism, having edited a student magazine at Essex. He’s actually been writing since he was a child, his first ‘novel’ (‘Adventure in the Peking Sea’, now sadly lost) scribbled in the last year of primary school – and he also studied piano, and has now segued to theatre (“drag queer performative activism, or aRtivism”), on which more later.

Andreas is a self-described “restless spirit”. He likes to talk, and talks fast. He seems to be both extrovert and introvert, enjoys interacting – his Parathyro interview includes his email at the end, urging people to get in touch – but also relocated to a mountain village in 2018, so he could write in peace and quiet. One of his favourite words (he uses it four times in our interview) is ‘intuitively’, which presumably is how he approaches the world: plunging in with emotion as a guide and his intellectual gifts to back him up, as he did with the Berengaria. “I always felt intuitively there was something there.”

That kind of sensitive temperament was an awkward fit in a small village school, at a time when boys were expected to be macho. Andreas wasn’t macho. He wasn’t exactly effeminate, but he didn’t play football and “didn’t talk about girls in that vulgar way, as a teenager”.

The family were quite working-class (his dad works in construction). He’s the eldest of four, which meant even more pressure. He wasn’t beaten up at school, but was bullied verbally on a daily basis – though he’s quick to add that “I don’t remember my childhood as being sad”. He’s actually quite opposed to the ‘victim narrative’ promoted by (some) LGBT organisations, which is partly why he’s now broken ranks with Accept – though it’s also, I suspect, his natural restlessness.

For a while, after coming out, he was very active, and very visible. “All of a sudden, I became an activist,” he says. “I was going to Pride, I was writing publicly.” He spent two years on the board of Accept, and two more as a kind of auxiliary member. Most of his media interviews were indeed for the Berengaria – but he also appeared, for instance, in Reporter in 2016, pushing back against homophobic comments by the then-Archbishop.

He worked as a researcher in NGOs (finding mentors at both Future Worlds Center and Equitas), then moved to the mountains because “I felt intuitively that it would help me with the book I want to write”. That’s actually a trilogy of novels on the LGBT experience, to be called When I Told the Truth – and you might say it’s both completed and not even started. He’s written down “all the ideas”, in the form of draft chapters and a mountain of notes, and also shaped it into a published play (Without Inhibitions) which had an online launch some time ago.

Still, as he heads into his mid-30s, the only widely-known work by Andreas – strange but true – is the history of a certain grand, possibly haunted hotel which he wrote in his teens, 15 years ago.

Why did he do it? Why, at 17, did he start a Facebook group called ‘Berengaria, We Want It Back the Way It Was’, which attracted some 2,000 members – mostly talking ghosts, admittedly, though also some historical nuggets – then visit the State Archives to find an entire folder on the old hotel, handling the fragile documents with special gloves? What was the “calling” that he felt, this still-closeted kid from a small village?

Hard to say – and in fact he can’t exactly say. But the Berengaria had a certain melancholy, which resonated with his own hidden sadness – and it also spoke of escape to a more elegant time, men in tuxedos and “French ladies with their hats and long dresses”. The hotel had been the venue for dances and beauty pageants. (He’s since met an old ‘Miss Berengaria’, now in her 80s.) Angie Bowie was a guest, before she married David. One old advertisement calls it the ‘Queen of the Mountain Hotels in Cyprus’, adding that guests “automatically become members of the famous Berengaria Knight’s Club, which stays open till 4am”.

Like Harry Potter (his favourite book at the time), the hotel spoke of magic, and a sense of something marginalised – like the still-hidden LGBT community – that was secretly magical. “I felt it, intuitively. I felt it. I knew it was something special, even before I did the research, before I discovered all these findings – back when everyone was saying ‘It’s haunted, it’s the haunted hotel’… Which made me so mad, I remember.”

The current renovation doesn’t make him quite so mad, in fact he has some good things to say about it. “It’s the first time I’ve seen so much professionalism,” he admits. “I talked to all the previous [projects] – and all I saw was the typical Cypriot village mentality. All I saw was peasants wanting to take a historic hotel and turn it into a casino…” He sighs unhappily, like a chef watching ignorant customers slather ketchup all over his creations.

Andreas is cautiously optimistic; still, he can’t help being protective sometimes. Last October, he recalls, he drove up to the site, to show a friend – and instantly saw that they’d taken off the roof, with winter coming. “It’s not like I go around saying ‘Hello, I’m the Berengaria writer’, I’m low-profile as a person in general. At that moment, though, I became ‘the Berengaria writer’!”.

In a panic, he tracked down the man in charge and was “very stern” with him, he says half-jokingly; “I was talking like I owned the place”. Eventually, the project manager assured him that a new roof was forthcoming, and Andreas calmed down.

It’s an odd situation, being probably the island’s foremost expert on the Berengaria – having amassed correspondence, old blueprints, yellowed leaflets, personal reminiscences – yet, at the same time, having nothing to do with it. Like all restless, intuitive people, Andreas doesn’t stay in one place – and in fact he’s already moved on, his latest ‘phase’ being perhaps the most liberating.

He’s taking a break from NGOs, actually working (ironically enough) in the hotel industry. The vague plan is to return to academia, for a PhD – but meanwhile there’s a new project, birthed in 2021 when, incensed by then-minister Emili Yioliti, he put on a blonde wig (to suggest her coiffure) and launched into a scathing satirical impression, uploading the video to general hilarity.

Since then, teaming up with an equally campy friend, he’s been putting out “drag political satire” into the world, a series of videos known as the ‘Banana Show’ where the cross-dressing silliness doesn’t quite conceal that “we have a lot of anger about what we see around us”, from nepotism to the Cyprus problem. “We [in Cyprus] have no culture, basically,” he sighs at Halara. “And we’re governed by incompetents.”

Andreas Andreou is quite young, and it’s fair to say he hasn’t settled yet. His greatest talent may be for connection – through his writing, and now performing – his deepest wish being to help other LGBT people find a measure of peace, as he did after coming out.

That’s the core – but of course there are other moving parts, other ghosts swirling around his psyche. Pride, and protests, and NGOs. Memories of school. Being called names, feeling friendless – and finding an unexpected friend in a faded queen of the mountain hotels, swept up by an inchoate “calling” to relate her glamorous history. People too, like hotels, can be haunted.

Click here to change your cookie preferences