By Flora Alexandrou

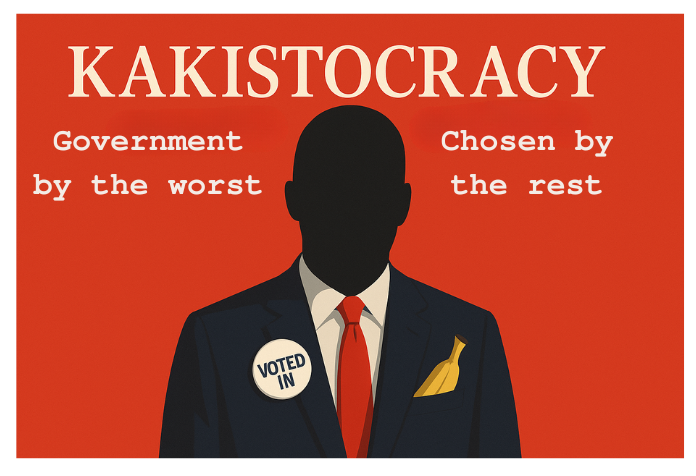

With its Greek-tinged tone, kakistocracy is a word familiar to some, unfamiliar to many, yet more relevant than ever and increasingly accurate in describing systems we still call “democratic”.

The political term, though not coined in Classical Greece (even if most “-cracy” suffixes trace their roots there), first surfaced in the 17th century. But it was only centuries later that it found its way into political theory, and eventually into academic and economic discourse. It refers to governance by the worst: the most incompetent, dishonest, unfit and, quite plainly, the stupidest.

What began as a pointed critique at the margins of political language has since evolved into a recognised diagnosis. In recent years, kakistocracy has crashed into public discourse. In 2024, The Economist even crowned it “Word of the Year”; an honour that captures the deepening global despair. Rule by the worst is no longer an exception. It is the pattern.

Of course, the symptoms vary by country. In mature or well-established democracies, kakistocracy emerges gradually, through institutional erosion or growing public cynicism. Elsewhere, in authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes, it is already cemented: a permanent system hiding in plain sight. Yet one thread runs through it all: power rewards the shameless, not the qualified.

And this is not just anecdotal. It is supported by data and research.

Political scientist Brian Klaas, in his essay “Why We Always Get the Wrong Political Leaders”, is one of many who argue that modern democracies elevate the least suitable candidates. “Power attracts those most likely to abuse it, and then makes them worse,” he writes.

All this leads to an inescapable conclusion: kakistocracy isn’t imposed. It’s chosen. Repeatedly, democratically, and with startling predictability.

Now that the term is, hopefully, no longer abstract, its relevance to Cyprus shouldn’t land like a punchline. It should hit like a slap in the face. Because this isn’t some foreign affliction. It’s familiar. It’s been ours for decades.

Which is why it’s time to stop normalising the absurd and take stock with a Cypriot Kakistocracy Check-Up, because for every point you silently agree with, it’s likely the system is more rotten than we dare admit.

Ten signs you’re actually living in a Cypriot kakistocracy

1. Positions go to the connected, not the competent.

(How many promotions can you think of that came from a handshake rather than genuine qualifications?)

2. Politicians trade favours for votes.

(Ever wonder why jobs and permits flood in right before elections?)

3. The education system doesn’t teach you how to think.

(Did they ever tell you Socrates was poisoned for making the youth think? Today, they just poison the system instead.)

4. The most qualified rarely wins. It’s the one with better lighting or more fake social media accounts doing the clapping.

(Who needs policy when you’ve got lighting, a borrowed slogan, or even a good priest confessor?)

5. “Not a total disaster” is considered a win.

(Ever wonder how low the bar is when basic competence gets applause?)

6. Some politicians struggle with the basics, yet run the country.

(Ever watch one on TV and think that if stupidity were taxed, he’d fix the national deficit?)

7. The “less bad” is still bad.

(How many times have you voted just to block someone worse?)

8. Negligence isn’t punished even when it costs lives.

(How many tragedies were buried under silence, excuses and committees?)

9. No one ever resigns, no matter what.

(How many scandals do you remember and how many does it take?)

10. Anacyclosis: the same discredited, recycled faces again and again.

(How do we “move forward” with the same people who dragged us backward?)

Now, score yourself:

0-3: You’re in denial.

4-7: You see it. You hate it. But you’re still hoping someone else will fix it.

8-10: You’ve stopped asking “How did we get here?” and started asking “Which country should I move to?”

So, this is how kakistocracy survives. Not just on corruption and incompetence, but on defeatism, on silence, on that collective shrug that says, “What do you expect? This is Cyprus.”

And if kakistocracy has become the norm, then perhaps the most dangerous thing isn’t who governs us. It is that, deep down, we’ve stopped believing we deserve better.

Or worse: we see the rot and choose to look away.

Flora Alexandrou works for the Spanish news agency EFE in Nicosia

Click here to change your cookie preferences