Similar to the rest of the Mediterranean and even the east coast of the UK from where I’m currently writing this, Cyprus has been experiencing some scorching temperatures this summer.

The average maximum temperature in Nicosia was 31°C as early as May this year, with the corresponding July average being a whopping 38.9°C. Coupled with one of the driest winters that the island has experienced in recent years, the antecedent conditions were ideal for what was to come.

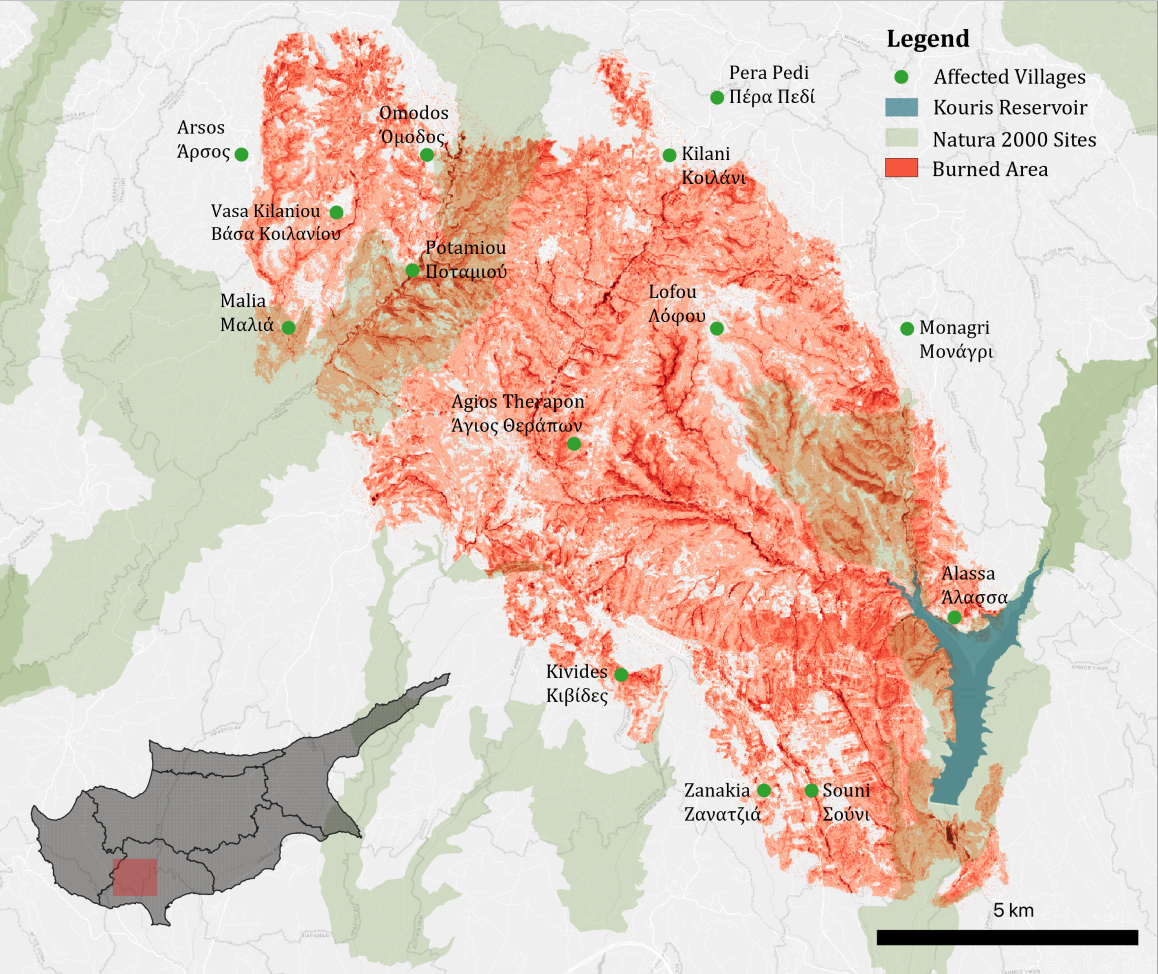

On the midday of Wednesday, the 23rd of July, the eve of the hottest day of the year, and while a high fire alert was in place, a fire broke out in the village of Malia in Limassol. By the next morning, the fire was well out of control, with multiple open fronts burning across the Krasochoria (Limassol’s Wine Villages).

By the time the fire was eventually put out by late Friday afternoon, it had burnt through 108km², an area almost as large as Nicosia (~111km²). This calculation is based on my analysis of satellite imagery using NDVI, though the government says 124km² were affected.

For context, the Arakapas fire in 2021, which burned a total of 55km² and destroyed 80 homes in 8 villages in June 2023 was, up until this summer, considered the worst fire in the island’s history.

In comparison, the July 2025 fire completely destroyed approximately 200 homes, caused damage to an additional (at least) 400 houses across 13 villages, killed 2 people and is now considered to be the worst fire in the country’s history. The flames destroyed significant areas of rich agricultural land as well as Natura 2000 sites, established to “safeguard Europe’s most valuable and threatened species and habitats”.

How does Cyprus’ climate create the ideal conditions for wildfires?

Just to be clear, I’m not here to tell you that fires in Cyprus are something new. Anyone who’s lived in Cyprus long enough, will tell you that summer wildfires have been a thing well before humans started bombarding the atmosphere with greenhouse gases. And it’s true that historically the Mediterranean climate is especially prone to wildfires due to the hot summers, dry winters and highly flammable vegetation.

It is also evident however that summer fires in Cyprus, and the whole of the Mediterranean for that matter, have been becoming more frequent and more extreme in the last years and decades. As the global climate is changing, the Mediterranean is experiencing the worst of it.

A decade ago, the world rallied around the Paris Agreement on climate change and the goal of holding global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Cyprus is already boiling

Being an island nation in the Mediterranean, any potential warming is deemed to have significant impacts for Cyprus, from sea level rise to more extreme heatwaves, and as we saw a couple of weeks ago, wildfires. What I found shocking about the coverage of the recent fires, and partly what triggered this article, was the lack of discussion around climate.

People seem to appreciate and share the view that we’ve had a hot summer and dry winter, but looking a bit more closely, the rate with which the climate in Cyprus is changing is already beyond even the extreme limits of what scientists were predicting.

The annual average temperatures recorded in Cyprus between 2016-2024 has been 1.35°C warmer than the average historical (1983-2010). July temperatures have been experiencing the most pronounced changes, with the average minimum and mean temperatures being 1.4°C and 1.65°C higher in modern times (2016-2024) compared to historical. To top that off, the corresponding maximum July temperature has been 1.9°C higher than the historical records.

What this means is that if you were sitting outside in Nicosia on a sunny July afternoon, it is more likely than not that the temperature will be 1.9°C warmer than it was 10 years ago. That’s 39°C compared to 37.1°C. Let that sink in.

Worth noting is that 1983-2010 is not even that long ago, and a comparison with the pre-industrial levels (1850-1900) would very likely have painted a much scarier picture.

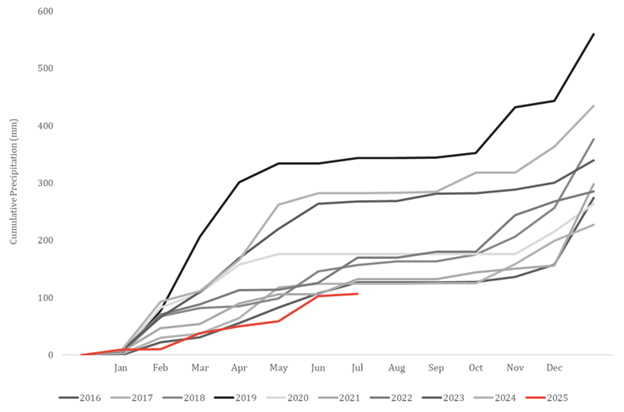

While long-term patterns don’t show a stark decrease in total precipitation over the past 40 years, the cumulative precipitation received so far in 2025 (up to and including July 2025) has been well below the records of the last decade.

The total precipitation received from January to July this year in Nicosia was 106mm. The equivalent for the years 2016-2024 was 198mm which means that so far this year we have received 53 per cent of what we did on average over the past 9 years.

The exceptionally dry year we’ve had so far is also reflected in the levels of reservoirs across the country, with the total water stored in the reservoirs as of August 1 being 50,061 million cubic metres less than the equivalent of last year. The average level of reservoirs across the island by the 8th of August was down to 16 per cent, significantly less than the already low 34 per cent equivalent of 2024.

Adapting, maladapting or not adapting?

Just two months ago, Konstantinos Letymbiotis, the government spokesperson, was boasting that the government was “at an absolute operational readiness with strengthened forces, modern means and clear strategy”.

In the wake of the deadly fires, however, Cypriots across the island have been questioning the government’s response, and the people have taken to social media and even the streets to express their disappointment and anger.

A delayed initial response to the first blaze, a delayed deployment of firefighting helicopters, community leaders having to ring church bells to warn residents that they needed to evacuate, no clear evacuation procedures and residents turning to social media in search of some guidance. All of these elements are probably no surprise to most Cypriots as we have been seeing this kind of response every summer, with the government often trying to pass the blame along and shift the focus to the fact that, once again, the source of the fire was arson.

The main difference this time around however was the speed and force of the flames, the scale and extent of destruction and the number of lives and livelihoods affected in the span of just three days.

The question is not how did the fire start, but rather is the government adapting its response to deal with the speed and intensity of modern-day fires?

Did Letymbiotis mean that by having “the most complete fleet, with the biggest number of aircraft in the history of the state, much earlier than other years”, we would be able to cope with a fire under today’s climate or under the conditions we knew two, five or 10 years ago?

Is the government really looking into how the climate across our island is changing? Are the fire alerts and state of preparedness informed by information beyond just tomorrow’s forecasts?

How can it be possible to issue a red fire alert and at the same time not implement the directive for the 112 line for emergency calls?

Maybe it all boils down to the Cypriot mentality of sticking with business as usual until something else happens that challenges our way of doing or, most of the time, not doing things.

In terms of spending, Cyprus in 2021 spent 0.3 per cent of its total expenditure on fire protection services. While between 2011 and 2021 most EU countries increased their total expenditure as well as their expenditure on fire protection services, Cyprus decreased its spending on fire protection services by 20 per cent, the biggest percentage decrease of all EU countries.

This doesn’t sound like a logical step for a country that in 2021 was more than 1°C warmer than it was in 2011.

In addition, Cyprus is currently not taking part in any of the 12 EU-funded wildfire prevention projects. It should therefore come as no surprise that despite the EU regulations regarding Public Warning Systems incorporated into Cyprus Law three years ago, these systems are yet to be deployed!

What’s to come?

As we are moving further into the Pyrocene – a new geologic epoch or age dominated by the influence of human-caused fire activity on Earth – climate projections paint a bleak picture for the Island. Temperature records are showing that Cyprus’ climate is already experiencing changes more extreme than the worst-case scenarios.

It’s clear that Cyprus has a choice of whether it takes concrete steps towards adapting to the already changing climate or whether it sticks with its business as usual mentality.

Just last April, The Cyprus Institute released a study showing that the minimum Cyprus would need to invest into adaptation until 2050 is €3.4 billion. That’s 0.4 per cent of the country’s GDP, which is not prohibitive to Cyprus’ economy, especially given the estimated potential savings from these interventions (€13.3 billion). Yet, until now, less than 30 per cent of these investments have been planned, let alone be implemented.

The actions that the government takes in the next few years will be pivotal not just for preserving what can be saved, but more crucially for ensuring that anything remains to be saved at all.

Athena Eftychiou is a climate change adaptation consultant based in London. In her spare time she’s either exploring the outdoors or knitting next to a cosy fire

Click here to change your cookie preferences