At the age of 78, David Ayres discovered a whole part of his family tree he had known nothing about

For many, a grave is a tangible anchor, allowing us to preserve relationships with loved ones long after they have passed. It is both a symbolic representation of enduring presence in our lives and a physical site for emotions that are otherwise intangible.

In Cyprus, the 1974 Turkish invasion and the island’s continuing division led to widespread damage and neglect of cemeteries on both sides. Headstones were broken, sites looted and remains scattered.

With custodians fleeing and burial grounds left unattended for decades, countless families lost track of graves amid the chaos of conflict, forced migration, and uncertainty surrounding thousands of missing persons.

Many would only locate the graves or remains of loved ones years later, as political restrictions gradually eased and visits became possible again.

Against this backdrop the story of David Ayres seems somewhat familiar. After searching hard, his family finally reached the cemetery in Trikomo, only to be met with the sight of a destroyed grave instead of the closure they had hoped for. But that grave, sad though it is, is actually the happy culmination of a chequered family history.

David is a 78-year-old man from the UK. He is married to Patricia Ayres and together, they have two children, Lisa and Max.

The investigation into his family tree began unintentionally, sparked by a commercial DNA test taken purely out of curiosity.

Yet the results delivered shocking revelations: the siblings he had grown up with were, in fact, half-siblings, sharing the same mother but not the same father.

The surprises did not end there. The test also revealed that David had two cousins in Cyprus: Constantinos in Larnaca and Costas in Kato Drys, the family’s ancestral village.

Eager to learn more, the family enlisted a genealogist, who returned with thorough research and a wealth of information.

She discovered that David’s father was one of three brothers from the Timinis family, also known by their patronym Miltiadou, in that village.

“Well, that was a bit of a shock, wasn’t it?” David said. “To end up 78 years old and find out you actually have a Greek dad. Which is unbelievable.”

Back in the mid-1930s, two brothers, Michalakis and Andreas Timinis-Miltiadou, left their village to seek new opportunities in London. They started by selling lace, but by the end of World War II, they had settled into running a cafe in Kingsbury, north London, not far from where David’s mother, Edna, lived.

It was likely at this cafe that Michalakis met Edna; a plausible scenario given the cafe’s proximity to both her home and workplace.

The cafe belonged to his brother Andreas, whose name briefly appeared in the newspapers in 1946 when he was fined for selling unrationed meat.

Soon after that incident, the brothers appear to have gone their separate ways: Andreas moved to Glasgow, and in 1947 Michalakis left London for Liverpool.

Whatever relationship he had with Edna ended around this time. No one knows now whether he ever learned of her pregnancy or of David’s birth.

In Liverpool, Michalakis found work at a fish and chip shop. One day, a colleague showed him a photo of his sister Maroulla. Struck by her beauty, he encouraged his colleague to send for her, determined to marry her.

True to his word, Michalakis and Maroulla married in Liverpool in 1949. Their first daughter, Elle, was born in 1950, followed by Despina in 1952. Since Maroulla hailed from Trikomo, the family eventually returned to her village in 1954 to raise their children together.

David and his family first travelled to Cyprus in May, eager to finally meet the two cousins they had been speaking with, Costas and Constantinos. DNA tests from relatives on both sides had sketched out parts of the family tree, but the most important branch, the one leading to David’s father, remained frustratingly blank.

After David’s family returned home to the UK, Costas and his partner kept up the search, reaching out to the local records office in the village of Kato Drys.

Their persistence paid off when they uncovered two key relatives: Miltios, a close cousin, and Despina, one of David’s two half-sisters. Both agreed to take DNA tests, which confirmed their family ties and ultimately led to the discovery of David’s father.

That breakthrough drew David’s family back to Cyprus, only this time not for a search, but for a reunion.

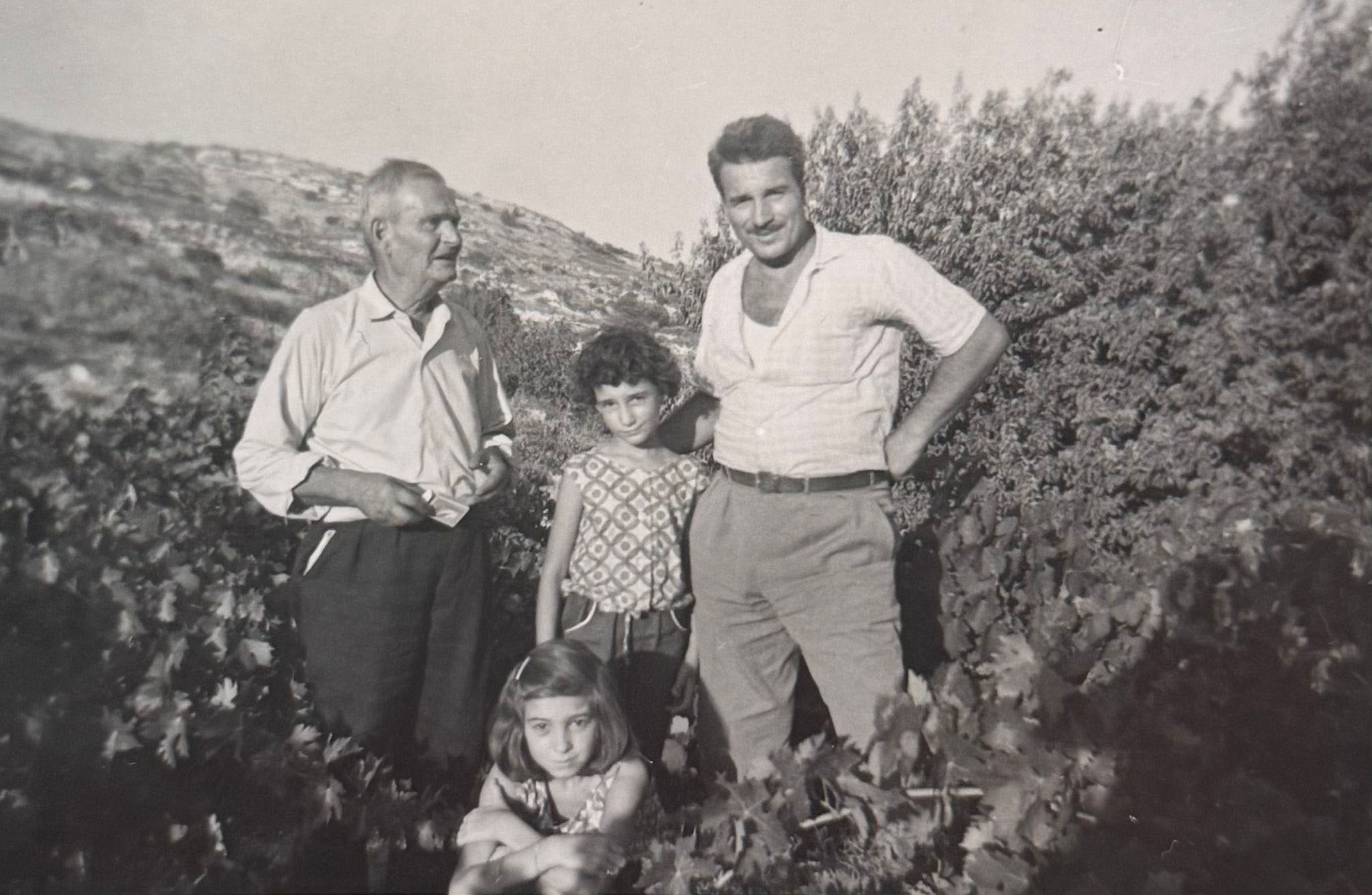

Seeing the family resemblance brought him reassurance. “We’ve got pictures of my dad, and we do look so much alike. So that’s why I knew he was my dad.”

David’s father, Michalakis Timinis-Miltiadou, had passed away in 1972, two years before the Turkish invasion of 1974 and was buried in a graveyard in Trikomo.

After a second family reunion at a house in Kato Drys, where David finally met his half-sister Despina, the family travelled to Trikomo to visit Michalakis’ grave.

What they found was shocking.

“The family knew the cemetery wasn’t maintained, but they didn’t realise it had been desecrated,” Patricia, David’s wife, explained. “The graves had been opened, every headstone smashed, mausoleums destroyed, and even some bones were lying around.”

The family tried to lift David’s father’s headstone, but it was impossible to re-erect.

“We were devastated when we saw the state of the graveyard. It’s just absolutely unbelievable and so disappointing to see that… I mean, I just can’t believe it.”

“Despina broke down,” David’s daughter Lisa added. “His sister was distraught. For many years she couldn’t visit the grave because of the war. And then to see it totally broken and smashed…”

After her father died and the invasion, Despina’s family moved to Athens. “Her mum was buried there,” Lisa explained, “even though she should have been in that family grave, with her own parents and husband. She never got the chance for that to happen.”

The family feels strongly about the condition of the cemetery and the dozens of others like it.

“They’re just desperate to do something, to get justice for the dead. It shouldn’t be like this,” Lisa said.

“For all generations to come, there should be a peaceful place to visit, a proper grave, a stone, somewhere for children and grandchildren. But instead, we saw nothing more than a building site.”

David added that while it is difficult for them to act all the way from the UK, the family remains open to suggestions and ways to help.

There are initiatives working to protect sites like these, most notably the bicommunal Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage (TCCH), supported by EU funding.

The committee brings Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots together to repair and preserve cultural heritage across the island, churches, mosques, monuments, and, more recently, cemeteries damaged or abandoned after the conflict.

Although the TCCH recently released a new list of cemeteries slated for restoration, the graveyard where Michalakis Timinis is buried is not yet included.

Still, the committee’s work, along with smaller grassroots efforts, offer some hope that more burial sites will eventually receive the care they deserve.

After all, graves matter deeply, not so much to the dead, but to the living.

So, while the Ayres family and their newfound relatives in Cyprus face grief, there is hope in the future and joy in discovery.

“We’re just a lovely, lovely family. We’re so pleased we found them,” David said.

Lisa reflected on how profoundly the reunion has reshaped their lives. “It’s changed everything for us. A whole new life. A whole new family. They’ve been so welcoming, taking us into their homes, giving us food, bringing gifts. It’s just been amazing.”

Next year, they’ll head to Athens to meet more relatives, and they hope to visit Cyprus often, maybe even buy a house there.

As they piece together fragments they never knew were missing and mend family bonds they never realised were frayed, finding a way to repair the graveyard in Trikomo remains an integral part of that journey.

Click here to change your cookie preferences