Lace and silk are representative of the island and faraway China. Both weave the history of their home with that of influencing cultures

By Karen Taylor

The famed silk roads, which connected ancient China to the rest of the world, were not so named until many years later, by German geographer Richthofen in the 1800s who reflected on the primary product sold on them: silk, produced in China since neolithic times. Centuries after they were first created, the routes and the fabric reached around the world, including the Mediterranean.

In Greece, the early Chinese were known as Serres, which led to the name of silk production, sericulture. These people were well known for their mulberry cultivation, the domestication of silkworms and the production of silk itself. Silk is today not only a symbol of Chinese culture, but also of its contribution to human civilization.

According to legend, the ancient Empress Luozhu, wife of the Yellow Emperor, considered one of the common ancestors for all Chinese, taught the Chinese people how to raise silkworms, although earlier archaeological finds point to a history dating back as far as the neolithic age. Either way, the Chinese people never lacked garments to wear.

The industry developed mainly in the Yellow River valley, where silk textiles were often exchanged in lieu of tax payments; during the Tang dynasty, each adult was required to submit two bolts of silk as tax.

Patterns grew increasingly intriguing and decorative as overland silk roads saw the fabric taken to the Eurasian mainland before heading further to the West while within one millennium the marine silk roads became an important force in the worldwide trade of silk and other goods. By the 18th century, Chinese decorative style spread through Europe, while patterns from the latter also appeared on Chinese silk. Meanwhile, silk became so precious a few garments could buy a European palace.

The development of the designs on silk resulted in silk textiles having great visual appeal; the variety of Chinese silk fabrics was immense. The earliest products displayed reflected their use in funerals and sacrifices with imaginary heavenly animals, while natural images of flowers, birds, insects and butterflies later became dominant before being overtaken by scenes of worldly life.

It is a message that remains today. “By telling China’s stories with unique aesthetics and attitude, I hope that the world will better understand and appreciate our traditional culture,” says silk scarf designer Fan Yanyan.

Serving as a bridge across various cultures, the silk roads succeeded in spreading China’s silk culture throughout the world. Delicate, lustrous and soft to the touch, the ethereal fabric has also threaded its way through China’s history.

On the other side of the world, a product that is as representative of its culture as silk is to China is the Lefkara lace, or Lefkaritika, of Cyprus, which also reflects a blending of cultures.

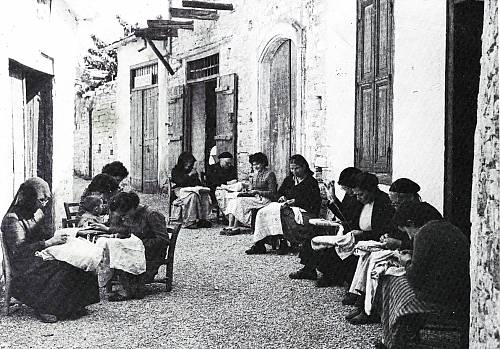

History shows that the tradition of lace-making in the village of Lefkara dates back to at least 1191 when the island was under the occupation of the Venetians. There are two theories of how it was created. Firstly, that the Venetian women graciously shared their skills with the local women; the second, and possibly more feasible, explanation is that the local women, in their capacity as cleaners and servants, would have come into close contact with the household linen of the wealthy Venetians.

Influenced by indigenous craft, the embroidery of Venetian courtiers, and ancient Greek and Byzantine geometric patterns, Lefkara lace is made by hand to very specific parameters. The lace always has a neutral colour, with both sides looking the same. The specific designs, of which there are about ten, mostly reflect aspects of nature, create light and shadow and, as they are geometric, can be interchanged. Single thread is always used and even the kind and quality is planned down to the last detail – French DMC cotton perlé in white, brown or ecru.

However, according to the Cyprus Handicraft Service the use of these basic designs has led to more than 650 different motifs. The most characteristic are rivers and zig zag arcs.

Lefkaritika soon reached a high quality because of the competition between women, since they were considered to be a centrepiece of a dowry. Meanwhile, men from the village, called kentitarides, travelled across Europe and Scandinavia to sell the product. According to tradition, its most famous buyer in the 15th century was Leonardo da Vinci, who visited the island and took a piece of Lefkara lace back to Italy with him, which today decorates Duomo Cathedral in Milan.

And, as with silk in China, it remains highly thought of. “Lefkaritiko embroidery is the most important thing in Cyprus in terms of art,” says Lefkara community leader Sophocles Sophocleous.

About Mirror of Culture

Mirror of Culture is a joint initiative of the Cyprus Mail and the Chinese embassy. It highlights the parallels between Cypriot and Chinese culture to set an example of acceptance, respect and

understanding among the various cultural communities on the island, recognising the fundamental importance of culture.

Culture is the universal language that transcends many barriers, including language and geography. The aim is to work with diverse cultural communities in Cyprus to share and promote our vibrant cultures to further bolster the bonds among all the people of Cyprus and celebrate the diversity of cultures in the world.

Furthermore, the initiative understands the importance of cultural preservation, which is an important way for us to transmit traditions and practices of the past to future generations.

Click here to change your cookie preferences