It is December 28, which means many of us are deep into the Season of Delusion, a magical period when grown adults behave like weird Elfies drunk on mulled wine. The population becomes convinced that the New Year itself will trigger a transformation into better, healthier and more organised versions of ourselves. An impressively unfounded belief, as evidence consistently suggests otherwise.

By this point in December, no one is fully mentally present, not even institutions. A vague collective optimism sets in as the calendar nears its artificial reset, fuelled by the “fresh start effect”. The New Year becomes a psychological clean slate for ambitious goals and promises that largely remain unchanged.

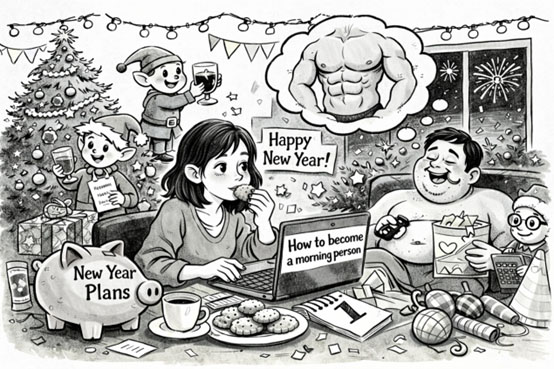

Somewhere in the final days of December, you are googling at 3.00am your New Year resolutions, including how to become a morning person. You, who once got tired tying your shoelaces, now declare, while eating kourabiedes, “this is my year of six-pack abs”. The tiny piggybank on your desk is already saving for your post-January reinvention.

Optimism in December is not a personality trait. It is a seasonal condition. And we all catch it.

Science offers an explanation. The festive period triggers shifts in “happy” neurochemicals such as dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin and endorphins, activated by food, nostalgia, lights, music and shared ritual. The result is Christmas cheer, a chemically enhanced sense that things are better than they actually are.

When hope reaches these levels, humans become capable of believing truly outrageous claims.

We even attempt to reorganise fate itself. In the festive mindset, we rearrange furniture, consult Feng Shui, cleanse spaces and burn candles. Even unpleasant events are considered flukes. A pigeon, in the festive spirit, poops on you, you step in the muck of a clearly very happy dog, and it is taken as a sign of New Year good luck. The coin in the vasilopita becomes a prophecy.

By now, optimism and a kind of collective hallucination, helped along by a persistent food coma, have detached from reality. Somewhere between bites of melomakarona, you hope that the president will emerge in the New Year as a leader of credibility and capability, that the church will confine itself to religion, that MP Andreas Themistocleous becomes a feminist, that Elam’s Christos Christou adopts a migrant Muslim family, and that Efthymios Diplaros earns a PhD in art criticism, with several more easily added to the list.

This is precisely where optimism stops being harmless and starts becoming tyrannical.

Part of the reason is that beneath the glitter and chemical cheer, December is exhausting. The pressure to feel grateful and joyful often collides with stress, financial strain, unresolved grief and burnout. By the end, many people do not feel renewed, only relieved that it is over.

December optimism, however, is not just personal. It is institutionalised and, in its polite form, becomes a quiet tyranny, offering an alibi to postpone accountability behind the promise of “next year”. The cost-of-living crisis and electricity prices are blamed on markets, wars or the weather, anything except policy. Housing unaffordability is naturalised, wages lag behind inflation, and Cypriots are told to wait for natural gas while reassuring ourselves that next year we might live like sheikhs. Hospitals struggle, scandals remain “under investigation”, and even the Cyprus problem survives as a familiar, sad New Year refrain, “next year to our homes”. Optimism curdles into frustration.

And we participate willingly. We suspend scepticism, outsource responsibility to the future and dress avoidance up as hope. It is easier to plan personal reinvention than to demand systemic change, easier to rearrange furniture than to confront power, and easier to imagine a better version of ourselves than to question why the same institutions justify, unbothered, the same failures every year.

By January, nothing will have changed. Except the decorations. Christmas lights give way to EU flags and curated symbols, reminding us that Cyprus holds the Presidency of the Council of the EU for six months, a role that unfounded optimism believes will turn the island into the EU’s “saviour”, while its own urgent challenges remain unresolved, or postponed to some other new year.

Happy Same Year to us all.

Flora is a foreign correspondent, investigative journalist & multilingual storyteller

Click here to change your cookie preferences