At the end of the 19th century a group of Russian dissenters arrived in Cyprus to settle. They were to last less than a year

By Alexander Larin

On August 26, 1898, 1,126 Russian Doukhobors arrived at the port of Larnaca on the French steamship Le Douro from Georgia.

After completing quarantine, 560 Doukhobors rented a 1,334-acre farm from the British colonial authorities in the Nicosia area. Known in Greek as Athalassa, the farm was called Efremovka by the Doukhobors. Despite having access to fresh water and fertile land, the harsh climatic conditions proved unsuitable, resulting in the deaths of many settlers from hunger, disease and exhaustion. Today, no traces of the Doukhobors’ presence in Athalassa remain.

Another 460 Doukhobors settled on a 106-acre farm in Pergamos (Famagusta). Here, they faced the same challenges: a subtropical climate, contaminated water and insufficient land for successful agriculture. Within nine months, many died, and in 1899, the Doukhobors left the area. Before leaving, they erected a memorial stone in honour of the dead.

A smaller group of 100 Doukhobors rented a 129-acre farm in Kouklia (Famagusta). Although fresh water was available, the land was again unsuitable for farming due to the harsh climate and insufficient space. Like in other areas, many Doukhobors died from hunger, disease and exhaustion.

In April 1899, with the help of English Quakers and Tolstoyans – followers of the novelist Leo Tolstoy – the necessary funds were raised for the resettlement of the Doukhobors from Cyprus to Canada. A total of 108 Doukhobors died during their time in Cyprus.

That is the brief history of the short stay of the little-known Russian Doukhobor community in Cyprus. But who were they? Why did they come to Cyprus?

The Doukhobors (Canadian spelling) or Dukhobors are an ethno-confessional group of Russians. Historically, they were a religious sect that rejected the external rituals of the Russian Orthodox church, by whom they are considered heretics.

After the schism in the Russian church in 17th century, many Russians began to distance themselves from traditional Orthodoxy. The pioneers of this process were the Old Believers, who became a symbol of resistance to church reforms and later to the Tsarist government. However, some groups went even further, forming movements that later became known as “Spiritual Christianity” or “Folk-Protestantism”. The Doukhobors formed their religious platform by drawing on Quaker ideas, and absorbing a number of ideas from Gnosticism and Freemasonry. These influences shaped their emphasis on inner spirituality, direct communion with the divine, and rejection of external rituals.

They rejected the church hierarchy, traditional rituals and the necessity of attending churches, instead emphasising personal faith. The Doukhobors do not venerate the Old and New Testaments. For them, the primary book is the “Living Book” which consists of psalms, hymns and beliefs and was shared in oral form.

A key characteristic of Spiritual Christians, especially evident among the Doukhobors, was their fundamental pacifism. They categorically refused to serve in the Russian Imperial Army, take up arms, or participate in military actions.

For the Russian Empire, communities of “non-Orthodox Russians” (as the authorities called them) posed a serious problem, as their existence undermined the official narrative of an Orthodox people loyal to the autocracy.

Beginning in the second half of the 18th century, harsh measures were taken against the Doukhobors as heretics: they were whipped, subjected to various tortures and entire families were exiled to hard labour, settlements or penal servitude.

Under the rule of Alexander I (1801-1825), the government’s attitude toward the Doukhobors shifted for the better. The government decided to resettle them from various locations to one central area and they were allocated steppe lands in the Melitopol district (modern-day, Ukraine) where they formed the first Doukhobor colony. In total, about 4,000 people were resettled.

The leader of the Doukhobors, Savely Kapustin, introduced communal rules, including communal cultivation of the land and equal division of the harvest. In 1818, Alexander I visited the Doukhobor village and stayed there for two days, after which he ordered their release from the oath of allegiance to the state.

When Nicholas I became Tsar in 1826, he issued a decree aiming to force the assimilation of the Doukhobors through military conscription, banning their meetings, and encouraging conversions to the state church. In 1830, another decree mandated the conscription of dissenters and the resettlement of their non-military members, women and children. Between 1841 and 1845, around 5,000 Doukhobors were resettled in Georgia.

At the end of 1886, the Doukhobors split into two groups. One accepted some concessions to the government, while the other, led by Peter Vasilevich Verigin, maintained a strong anti-military stance.

Verigin was exiled, where he immersed himself in reading, corresponded with Tolstoy and the Tolstoyans, and became deeply influenced by Tolstoy’s ideas on non-violence, vegetarianism and the pacifism of the Quakers. The next phase of Verigin’s worldview was marked by his directives to the Doukhobors: they should not swear allegiance to the tsar, refrain from harming any of God’s creations, and, consequently, not participate in war.

The most striking manifestation of Doukhobor pacifism was the act of mass burning of weapons, carried out in 1895 in Georgia. This act became a powerful symbol of their protest against military service and marked their final break with the old order. However, it ended in tragedy: 4,300 were deported to remote areas of Georgia without the right to sell their property, some were imprisoned and sent to disciplinary battalions, while others were exiled to Siberia, where many later perished.

To escape further persecution, many Doukhobors were forced to leave Georgia. With the active support of Tolstoy and other public and religious figures from Europe, efforts were made to organise the emigration of some Doukhobors to Canada. Between 1898 and 1899, around 7,500 Doukhobors left the Russian empire, primarily settling in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

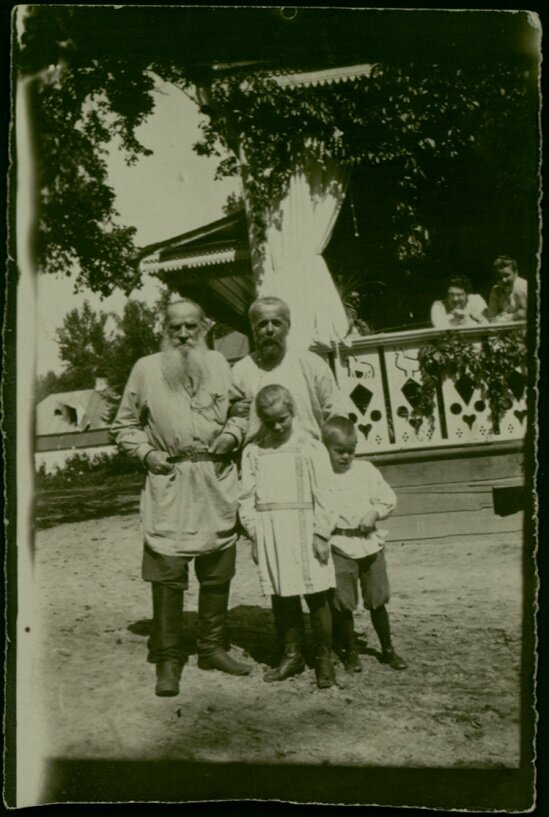

Tolstoy was not only a renowned writer, educator, philosopher, and public figure, but also a key advocate for the Russian Doukhobor community. His efforts to support the Doukhobors led to their emigration to Canada, although some first tried Cyprus. Tolstoy dedicated several years to their cause, writing letters to authorities, signing appeals to the international community, and publishing articles in his newspaperto raise funds for the Doukhobors. He even sent an open letter proposing that the Doukhobors be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

According to Tolstoy’s estimates, at least three hundred thousand rubles were needed for the resettlement of the Doukhobors. To raise this amount, Tolstoy decided to publish his novel Resurrection and the story Father Sergius, using the twelve thousand rubles from their proceeds to fund the relocation. The Quakers also played a significant role in organising the resettlement.

A group of 1,126 Doukhobors came to Cyprus in August 1898. Life on the island was difficult from the start, and just months later, the exhausted and weakened Doukhobors, suffering from a debilitating fever, had to be evacuated to Canada, where other members of their community had already settled.

Whilst in Cyprus they were joined by the supporter and biographer of Tolstoy, Pavel Ivanovich Biryukov. His observations were published in an article, “The Doukhobors in Cyprus” in Svobodnoye Slovo. According to Biryukov’s report, when the Doukhobors landed, aboard the French steamship Le Douro, the island seemed promising. Cyprus was beautiful, with fertile soil, lush vegetation and a seaside climate that reminded them of their homeland. The only drawback, at first glance, was the lack of housing.

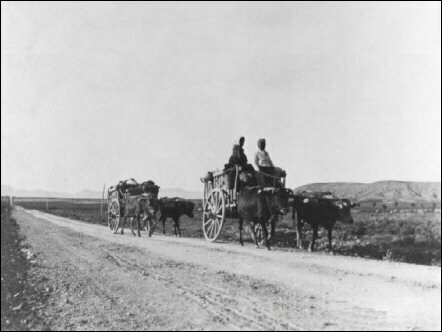

After several weeks of quarantine in Larnaca, the Doukhobors were resettled in three locations: Athalassa, Kouklia and Pergamos. They began to build small agricultural settlements, constructing mud-brick houses in the Caucasian style and preparing the soil for planting vegetables. However, by autumn, it became clear that the resettlement did not meet the expectations set by the Tolstoyans and Quakers who had supported the Doukhobors. Disagreements arose within the community regarding farming methods, with arguments over the value of collective versus individual farming. The lack of strong leadership and difficulty adapting to new conditions further complicated the situation.

Despite good intentions, the Russian Tolstoyans, including Biryukov himself, did not fully understand the local conditions. As a result, neither construction nor agriculture progressed as expected. Many Doukhobors continued to live in tents, which were located in swampy areas teeming with mosquitoes. Those who managed to build homes faced cramped and unsanitary conditions.

The problems were worsened by a limited diet – vegetables had not yet ripened, milk was only available in condensed form, and meat, forbidden by their religious beliefs, was not consumed. Poor drinking water and a harsh climate led to outbreaks of serious diseases. Two months after their arrival, the first deaths occurred. Within a few months, 108 people had died from hunger, disease and exhaustion – resulting in a death rate even higher than during their exile in the Caucasus.

“As I observe life in Cyprus now, I can say that the thought of permanent settlement of the Doukhobors in Cyprus, if such an idea was actually entertained, could only have occurred to a person entirely unfamiliar with Cyprus or someone understanding nothing about the living conditions of the Russian peasant,” wrote Biryukov.

By the end of 1898, the Doukhobors’ hopes for the resettlement had faded. Biryukov urged them to leave Cyprus, deeming it the only option to avoid complete extinction.

Another supporter was wealthy evangelical turned Baptist Ivan Stepanovich Prokhanov. In 1898, at the request of English Quakers, Prokhanov travelled to Cyprus to assist the Doukhobors. For several months, he worked among the settlers, providing medical care and helping with their food and housing needs.

In 1933, Prokhanov published an autobiographical book titled In the Cauldron of Russia: A Life of Optimism in the Land of Pessimism in Berlin. The book was published in English.

Here are some of Prokhanov’s memories from his book about Cyprus:

“The population of Cyprus consisted of Turks, Greeks and Armenians. The tall and handsome figures of the fair-featured Doukhobors were conspicuous among these natives.

“I found the Doukhobors in a very sad condition. Most of them were ill with a strange disease, something like dysentery. A man would have blood issues, some swelling on the legs and in a few days he would die. Entering one of the barracks, I saw a low wooden platform built along one wall for the full length of the room, on which they usually slept, but on which now there were sick people lying, with some dead bodies in between them! About one hundred men and women had already died. A Russian cemetery had been made a short distance from the Doukhobor colonies.”

Yet another supporter was Leopold Antonovich Sulerzhitsky, the Russian theatre director, artist, teacher and an associate of KS Stanislavsky. He is also known as a friend of Leo Tolstoy’s family and a key participant in the resettlement of the Doukhobors from the Caucasus to Cyprus and Canada.

In 1898–1899, at the request of Tolstoy, Sulerzhitsky organised the resettlement of the Doukhobors to Canada.

In 1905, Sulerzhitsky published an autobiographical book, To America with the Doukhobors. This diary-style book narrates the story of the resettlement of 7,300 Doukhobor peasants to Canada in 1898–1899. It includes a chapter dedicated to Cyprus, titled “The Island of Cyprus”, where Sulerzhitsky recounts how the Doukhobors left the Mediterranean island.

Here are some of Sulerzhitsky memories from Cyprus.

“On Friday, April 11 [1899], a pink stripe appeared on the horizon in the morning. It was Cyprus.

“As we drew closer, we saw that the entire island consisted of barren orange sandy cliffs, covered with dazzlingly white sand. The sun here scorches like in the tropics. The sea around the island is a brilliant turquoise. All of nature—the dark blue sky, the lazy turquoise sea, and the island sparkling so intensely it almost hurts the eyes—is saturated with the scorching rays of the sun.

“There was not a breath of wind in the air. The heat radiated from the red-hot stones and sand, growing more intense as we approached the island.

“The Doukhobors had arrived on the island in August, totalling 1,126 people, and in just seven months, more than 100 had died, mostly from the terrible local fever.

“Cyprus fever is nearly incurable, affecting not only humans but even horses, dogs, chickens, and other animals. Every living thing on the island is subject to this dreadful scourge.”

On April 27, 1899, the Doukhobors departed Cyprus aboard the steamship Lake Superior, crossing the Atlantic to join their fellow Doukhobors in Canada. Thus ended the unsuccessful experiment of resettling the Doukhobors on a Mediterranean island.

The Doukhobors who resettled in Canada in the late 19th century, including those from Cyprus, founded communities on virgin lands in the province of Saskatchewan. The Canadian government allowed them to avoid military service and allocated land for collective farming, provided it was used for agriculture. However, when the authorities required the Doukhobors to swear an oath of allegiance to the government, many refused. As a result, 260,000 acres of land previously cultivated collectively were confiscated. From 1908 to 1911, around 6,000 Doukhobors moved to British Columbia, where they founded the Christian Community of the World Brotherhood. This community flourished, with its communal property valued at several million dollars.

As of 2021, 1,675 people in Canada self-identified as Doukhobors.

Click here to change your cookie preferences