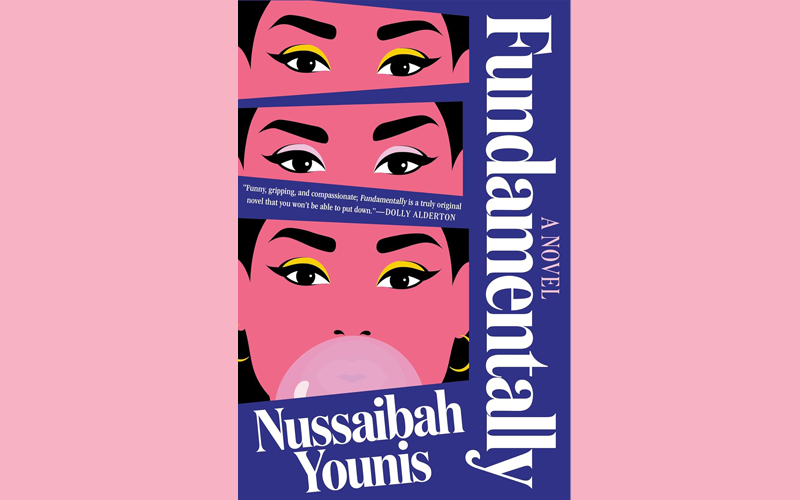

Fundamentally by Noussaibah Younis

Onto another of the shortlisted novels for the 2025 Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse prize for comic fiction. This time, a debut from academic and peace-building practitioner (that’s what her bio says) Noussaibah Younis. And, following the befuddlement aroused by Rosanna Pike’s A Little Trickerie, it came as something of a relief that Fundamentally was both funny and intended to be so. I mean, who doesn’t like jokes about ISIS brides and dysfunctional UN workers? (Obviously, if the answer to that question is you, then don’t bother reading on; this won’t be the book for you.)

Nadia’s been rejected by the woman she considered the love of her life and has a strained relationship with the mother who disowned her at 20. Naturally, then, the only thing to do is accept a job offer from the UN to go to Iraq and run a deradicalisation programme for ISIS brides.

Upon reaching Iraq, Nadia is forced to confront not just her own complete inadequacy for the gig, but also the fractiousness and committed irrationality of the UN, staffed by gay French aristocrats, child-abandoning UNICEF department heads, Geordie beefcake security officers, and the equal parts ludicrous and legendary Sherri, who believes that ‘yoga is a basic human right’, is currently ‘trying to decolonize [her] sexual preferences’, and finds it ‘offensive to assume that a cis straight white woman is a cis straight white woman’.

All of this fades into insignificance when Nadia becomes obsessed with Sara, ‘a hijabi rude girl from Mile End’ whose daughter has been taken from her by the parents of her deceased ISIS-member husband. So dedicated is Nadia to Sara’s cause that she ends up getting herself fired, stealing Sara from one of the most powerful men in Mosul, and illegally smuggling her out of the country.

The only problem (well, not the only problem; as you might imagine from the description above, the whole thing is fraught with problems) is that Nadia never really asked Sara what she believed, so she very quickly starts having to question whether what she’s done might actually not have been for the best after all.

Through all this, Younis wittily explores and exposes the lunacy and egotism at the heart of so many enterprises that might be labelled noble, in a plot that is pacy enough to keep any reader engaged, and with a sharpness of phrase that pleases the ear. Sure, there’s the odd clunky punchline, and some moments of silliness that don’t quite land. But unless you’re one of the humourless pedants that Younis rather aggressively attacks in her afterword who don’t like the idea of making jokes about serious subjects, you can’t fail to have a good time.

Click here to change your cookie preferences