Now, I can’t pretend to have read any of the Icelandic sagas or eddas, which are the literary works in whose tradition All the Horses of Iceland purports to follow, but what I can say of Sarah Tolmie’s novella is that after having read it, I am now more likely to try and fill in my Icelandic ignorance than I was before.

Narrated by a Christian scribe called Jor, All the Horses of Iceland tells the story of Eyvind, an Icelandic merchant who – like all Icelanders, according to him – aspires to become a farmer ‘in a land far from any king’. In pursuit of these ambitions, Eyvind becomes part of a Khazar trade caravan working a route across the Eurasian steppes. While staying with the leader of a wealthy nomadic tribe, Eyvind inadvertently discovers his possession of just enough white magic to help rid the tribe of its haunting by Borte, the leader’s deceased wife. His reward takes the form of 25 horses – enough to make Eyvind a very wealthy man back in Iceland, if he can only navigate the war-torn territories that lie between him and home.

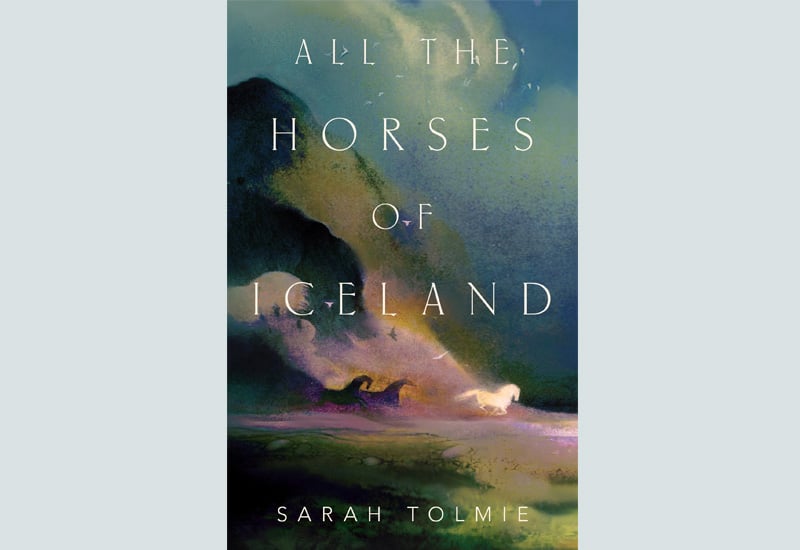

One of Eyvind’s 25 horses is a white mare – despite the fact that the nomads possess no white horses. Fairly obviously, the white mare is magical, and her magic allows Eyvind to negotiate the various political and military dangers that threaten his journey back to Iceland. Also fairly obviously, it is this unnamed mare that gives the novella its title, since she is the horse from which all Icelandic horses are said to be descended in the book’s mythic premise.

Ultimately, All the Horses of Iceland succeeds because of the spare and delicate prose with which Tolmie constructs the story, and the moments of vivid imagery and resonant, albeit truistic, dialogue, which might best be summed up by Borte’s mother’s line to Eyvind: ‘Living is an unlikely business’. It is this message that forms the thematic backbone of the book, with Eyvind showing that an ordinary man can thrive and live a life that benefits both himself and others, despite being imperfect physically – Eyvind is both sterile and partially deaf – and morally – most of what Eyvind does, he does out of ambition and expedience. The honest ambiguity of the happy ending elevates the book from something pleasant but fairly forgettable, to a story one feels glad to have read.

Click here to change your cookie preferences