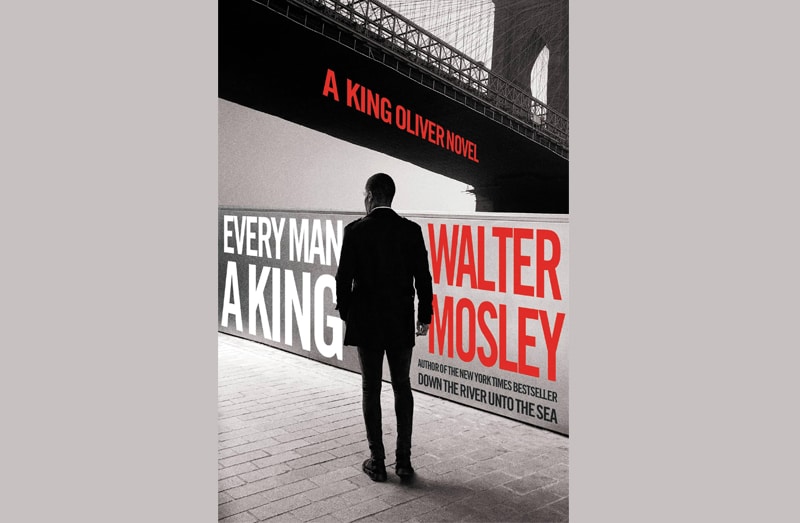

I don’t know what it says about the depth of my Raymond Chandler fandom that I find even a poor imitation to be worth reading. Maybe I should deride Every Man a King for trying so hard and falling so short of the standard set by the author whose influence echoes through the pages of Walter Mosley’s latest detective novel. But the truth is, despite the sometimes comic clunkiness, I had a good time.

Joseph King Oliver is a former NYPD cop turned PI who is pulled into two jobs he would rather have turned down thanks to his staunch affections for the two women he won’t betray. The first woman is his grandmother, Brenda Naples, whose boyfriend is the multi-billionaire Roger Ferris. When Ferris asks Oliver to look into the potentially illegal detainment of Alfred Xavier Quiller, polymath and alt-right ideologue, Oliver feels obliged to accept the gig. The second woman is Oliver’s daughter, Aja-Denise, for the sake of whom Oliver agrees to investigate the arrest of his ex-wife’s self-important new husband, Coleman Tesserat.

What we then get is a nicely interwoven double plot, filled with a cast of awesomely named but not always skilfully sketched secondary characters. These include Oliver’s friend Melquarth Frost, an improbably wealthy ex-master-criminal-turned-antique-watch-restorer who maintains a range of secret hideouts and is always happy to lend a hand, whether with shelter, money or violence. Oliver repeatedly insists on Frost’s sociopathy, but there’s never any sign of it, nor is it particularly important other than to impress the reader with Oliver’s toughness and ability to find the inner humanity of all men.

And herein lies the root of the problem. Mosley tries so hard to do Chandler, whether it’s with similes that he would like to be elegant lightning, but which often splutter awkwardly like, ‘He smelled like a lunch-bucket worker in wood scented by varnishes and wax, sawdust and powerful soap’, or with the random and pointless appearance of a Brasher doubloon. But the centre of Chandler’s novels is a detective whose compelling inner life is developed with total economy. Mosley’s detective is so full of emotional telegraphing (I think I got sick of his self-pitying and self-aggrandising references to Oliver’s traumatic experiences in Rikers after the third such moment) and tediously drawn-out inner monologues (why would anyone need to hear Joe Oliver’s platitudinous philosophising on the subject of gift-giving?) that he just isn’t hard-boiled. Lord help me, and forgive me for the pun, but he’s at best over-poached.

It’s simple really. If you haven’t read Raymond Chandler, go read him. If you have – and you liked it – you’ll probably have a decent time with Every Man a King.

Click here to change your cookie preferences