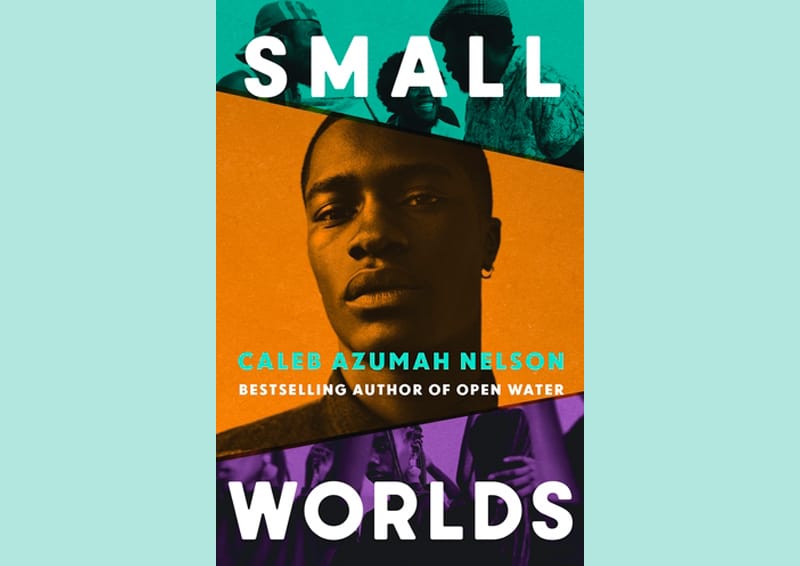

Following up a debut as striking as 2021’s Open Water was always going to be a tough ask. Caleb Azumah Nelson’s second novel Small Worlds returns to the themes of young love and what it means to be young and black on the streets of London in the 21st century. Unfortunately, though, it doesn’t return to the compelling tightness of his debut.

The problem is one of too much ambition and too little precision. The novel’s first section deals with the relationship between Stephen and Del, both second generation immigrants in their final year at secondary school, as they deal with the anxiety of waiting for exam results and university offers while exploring the jerky but beautiful transition of a childhood friendship into a young adult romance. This is the section where we meet the novel’s cast of characters, all of whom are deftly drawn and burst into the reader’s imagination, from Stephen’s parents whose example teaches him ‘that a world can be two people, occupying a space where they don’t have to explain’, to his brother Ray whose infectious personality and womanising mask his deeper worries, to Auntie Yaa who owns a shop that gives Afro-Caribbean immigrants a space to be and to taste something of home.

Section one is the book’s highpoint, often brilliantly evoking the nostalgia and nervousness inherent in that final summer of school, and introducing the verbal refrains that echo throughout the novel. What happens subsequently, however, as Azumah Nelson jumps to the London riots following the shooting of Mark Duggan in 2011, to Stephen’s trip back to Ghana following a tragic personal loss, and through Stephen’s estrangement and reconciliation with his father, adds too much and too little. The same refrains echo throughout, but the pitching and timing are off; instead of tying the whole thing together, they get repetitive and flabby. Meanwhile, the depiction of London’s incendiary atmosphere and Stephen’s trip to Ghana feel like shallow if sincere attempts to add depth and weight to the novel.

Ultimately, Small Worlds just feels a little undercooked. The musicality of Azumah Nelson’s writing is still evident, but it hasn’t been refined enough to sing out a perfect whole. In Small Worlds, just like in Open Water, the narrator finds himself repeatedly commenting on the inevitable failure of language, but whereas in Open Water the reader is made to wryly smile at the irony of a virtuoso user of the language commenting on its limitations, in Small Worlds, when Stephen comments that language ‘has always struck me as less tool than burden’, it feels contrived and more true than the reader would like.

Click here to change your cookie preferences