Are you Fckng Serious? Injured as a child, one international DJ in a mask took refuge in his creativity, and his life as a normal guy

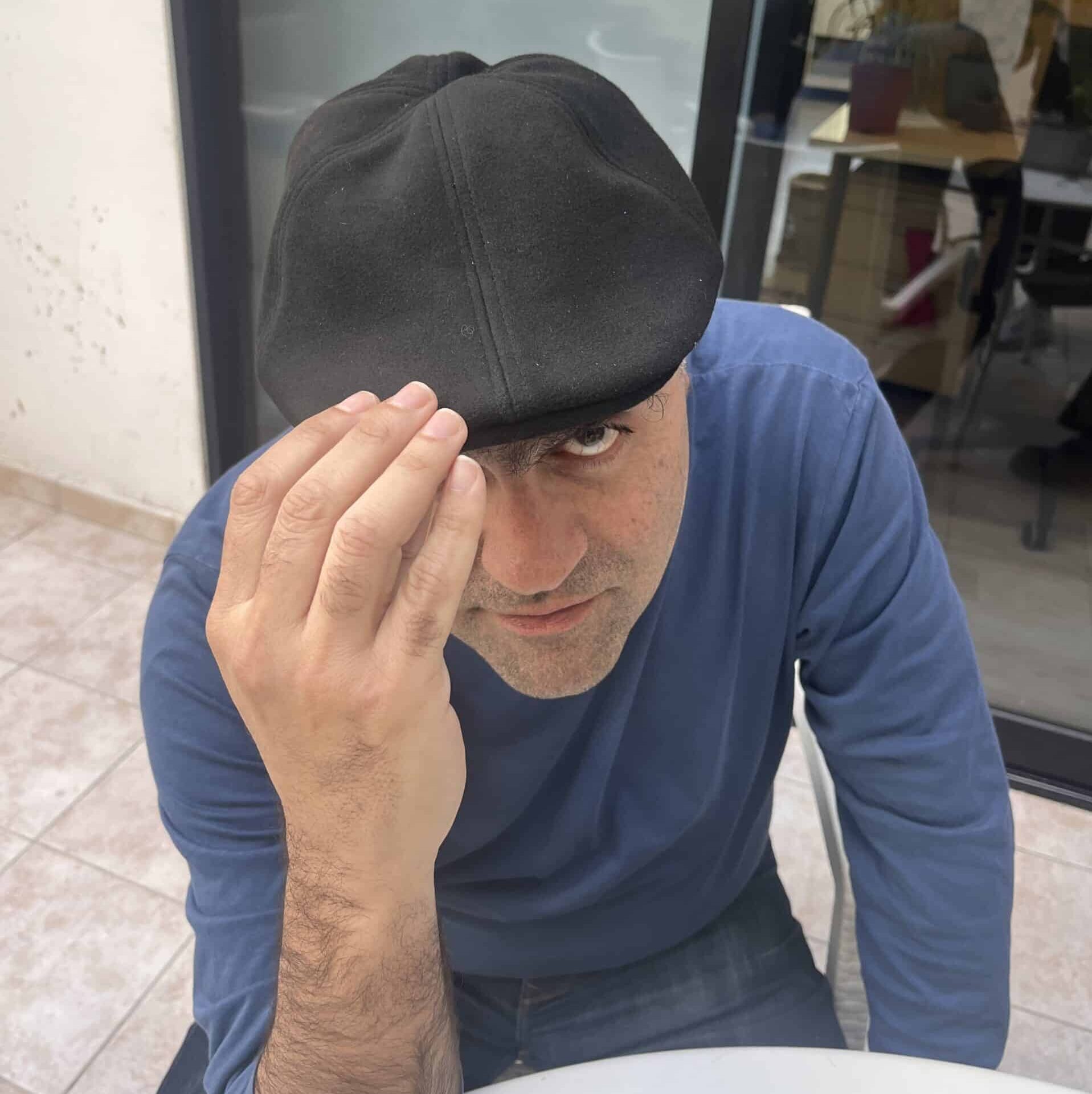

You can’t really tell over a Zoom call. Only when the angle’s just right, when he inclines his head a certain way, can you make out… something on the side of Boris Brejcha’s face, a patch where the skin seems unnaturally stretched.

That’s the only visible sign (facially, at least) that Boris – one of the world’s premier DJs, and one of the stars of the BEONIX electronic music festival in Limassol this month – almost died in the Ramstein air show disaster 37 years ago.

It was August 1988. He was “six years young,” as he puts it (he was born November 1981), living with his parents and sister in Ludwigshafen, near Mannheim in Germany. They went down the road to the USAF Ramstein air base, where a huge crowd had gathered to watch a display by Italian Air Force jets. “And then they crashed,” says Boris. “And we were standing in [the] front of the crowd, and so I got burned.”

He remembers the moment in flashes. He recalls his sister having fled a few seconds earlier, as though she’d had a premonition. He recalls the crash, “and I was running, running, then I was falling to the ground” – that’s what caused the facial burns – “then I was standing up again, I was running. And there was a girl, she caught me and put me in a helicopter, to fly me to the hospital…” 70 people died in the disaster, while 346 were seriously injured.

Boris was among the latter, hospitalised for three months and forced to wear a facial reconstruction mask in what must’ve looked like a kiddie version of the Phantom of the Opera. “I was just starting school,” he recalls with a sigh – “and the little children, they never lie, they just say the truth.”

Fellow six-year-olds wasted no time in making him feel like a freak – and of course the scars remained even later, in adolescence, when appearance is so all-important. “I mean, it was hard in school,” he admits. “I had no friends, really. I was most of the time just alone.”

Did he sink into depression? Oddly enough, no. It helped that he was young, so it almost felt like he’d been “born with it”. (He’s watched documentaries about the accident, and people who were already adults struggle with trauma even now.) He also seems to have been a naturally upbeat child. Even while in hospital, according to his dad, “I was super-positive. I was singing all the time, I was running around”.

And of course there was also another factor.

“I was searching for something – um, like a doctor,” explains Boris in his Germanised English. “So I started to make music – and doing the music was kind of my doctor, because I could do whatever I wanted, and talk how I liked with the music… Making the music was healing me.”

He shrugs, the tops of trees visible through a window on the screen behind him. “I mean, I don’t know if I would be a musician if this accident had not happened.”

He played drums for years, including a stint in a rock band (his dad – who’s now part of his entourage – had also been a drummer), but longed to perform his own songs, not just covers, and also wanted more control, to “make everything by myself”. Boris is unusual in DJ circles for playing all his own compositions (no samples) – and he’s also a producer with his own record label, the amusingly-named Fckng Serious.

It’s a bit simplistic to trace everything back to the accident. He is, after all, so successful, No. 55 on last year’s list of the world’s top DJs (as ranked by DJ Mag). His top YouTube video has 63 million views. His biggest-ever crowd was around 70,000, at EBC Las Vegas – but he plays sets constantly, almost every week, and they’re all big venues. BEONIX is sandwiched between two dates from his Reflections tour (he’s actually playing in Berlin the night before). Later, in December, he’s off to the southern hemisphere, for an extended tour of South America.

Then again, it’s hard not to trace everything back to the accident. Take the fact, for instance – by far the most obvious fact about Boris Brejcha – that he wears a mask, variously described as a ‘Venetian mask’ or a ‘Joker mask’, while performing.

“This is not because I am burned,” he insists. It’s just a part of the persona, like the autographed rubber ducks – another Boris trademark – which he’ll hand out to people in the front rows. His appearance isn’t some big mystery, and he usually takes off the mask halfway through a set. Still, the echoes of his childhood disfigurement are unmistakable.

Then there’s the music itself, a sub-genre known as ‘high-tech minimal’ – which of course is subjective, but mostly comes across as calming, feelgood, hypnotic music. Asked which tracks he’d recommend for newbies, Boris cites ‘Gravity’, ‘Purple Noise’ (his personal favourite) and ‘Take It Smart’ – though electronic music is a journey, and you’d really have to listen to a full three-hour set to get a sense of it.

“Maybe this could also be because of the accident, I dunno,” he admits, speaking of the vibe he creates through his songs. “Because when I’m in the studio, and when I produce music, I produce music [that reflects] how I feel.” Often – and without really planning to – what he produces turns out to be buoyant and melodic, “like you can fly, and have a good time… Maybe it’s something I’m still working on myself – to take this accident away, I dunno.”

Then there’s his lifestyle, and work schedule, and general demeanour – all of which are entirely fine and positive (he’s very open, and easy to talk to), yet also consistent with a man who’s spent his life building up a wall to contain trauma.

We talk on a Tuesday, which is by design (his design). It would usually be Monday, his “office day” – a day for paperwork and pesky journalists – but the show was a day late this weekend. “We try to do shows only on Friday and Saturday, coming back on Sunday. Then I have a whole week at home, I can relax or go in the studio.”

It’s not a rigid system, of course. His BEONIX show, for instance, will be on a Sunday (the 21st), and of course the schedule will change while in South America. Generally, though, Boris’ life is structured – and that’s also by design. World’s biggest DJ on Friday and Saturday, back on Sunday, office day on Monday, “and then Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday I’ll go to the studio. This I do every week, and I love it.”

The house is near Frankfurt (to be close to the airport); “We have just one neighbour, and the rest is forest. It’s really cool”. The studio is a separate building, next to the house. Boris loves making music – “I just go to the studio, start something, and see where it takes me” – and does it constantly. He’ll finish one track a week on a normal week, usually playing it at the show that weekend.

Is it normal in DJ circles to produce a new track every week?

“No,” he admits. “It’s just because I’m a nerd!”

He is quite nerdy, in a rather delightful way for a man of his celebrity. Rave culture has always been drug culture but he’s never tried hard drugs, not even once. Fans may be startled to discover that behind that slightly forbidding mask lurks a laid-back, unpretentious type who loves family life – “I have my girl, I see her every evening. We chill, it’s nice” – and a good game of footy.

“I really like playing soccer. We do that every Tuesday, we have like a ‘men’s night’ so we go and play soccer, or sometimes bowling.” He also enjoys tinkering with his website, replying to messages from fans on Instagram – actually, he adds, they quite often message to thank him for helping them “through a hard time with my melodies”, which is “super-nice” – hanging out with friends, or just sitting outside in the garden sometimes, “just do nothing and look into the sky…

“I’m just a normal guy,” says Boris Brejcha. “I mean, everyone is a normal guy. No-one’s like, super-super-better than the other.”

Is that true? Well, yes and no. A DJ, after all – just by the nature of the job – is the very opposite of a ‘normal guy’.

A DJ is a kind of shaman, magicking a crowd with his beats. It’s a strangely solitary form of musicianship: the DJ has control, and there’s also a distance there (Boris wearing a mask adds even more distance). A DJ won’t typically banter very much with the crowd, nor do DJs typically hang out together in the style of old-school rock musicians who’d go on the town and jam together after a show. “Of course, if you see some DJ backstage, you go to them and say hello,” says Boris. “But it’s not like you’ll be sitting talking with them for one or two hours… Maybe it’s just me, I dunno!”

A DJ, in short, represents a kind of bubble-world – which is also true for electronic music in general. What, after all, is the aim of this music?

“I would say,” he replies thoughtfully – “I mean, I started to produce this music to heal myself – but I would say the most important thing is for people to go to the party and just have a good time. Because there are so many negative things happening in the world – so the most important thing is to just think about nothing, and have a good time.”

Electronic music is escape, it’s oblivion. It’s not rage, like rock and punk. It’s not freedom, in the cerebral way of jazz. It’s not overtly about revolution, like hip-hop.

Is this healthy? Boris sighs at the question – then admits that, for the past year or so, he’s actually stopped watching the news altogether. He used to follow everything, he says, all the injustice and bloodshed in the world – “but then after a while I was feeling that, if I watched the news every day, it made me super-super-negative.

“And that’s why I decided not to watch any news – and I have to say life is much, much better.”

It’s a bubble, like his personal haven in the forest near Frankfurt. It’s a kind of mask, placing distance between himself and the world. Some may feel it goes too far. Boris, for instance, has performed on both sides of the Green Line (he played a set at the Ataturk Stadium in northern Nicosia in 2023), and got some abuse for it – “but I mean, I go there to make music, and to make the people happy,” he explains. “That’s my job. And not to get involved in political things, in my opinion.”

Is it right to not get involved, with so much going on in the world? But the DJ’s role is bigger than that. Tribes have always needed a shaman, someone to put the people in a joyful headspace – and electronic music is a force for good in that respect. In all the 18 years he’s been playing, notes Boris, he’s only ever seen one fight in the crowd, and even that was broken up in five minutes. The vibe just isn’t angry like that.

He himself was always the quiet type, the nerd, the solitary kid taking refuge in creativity. “Before I started to be a DJ, I’d never go to any club or anything. For me, it was better to stay at home making music.” Healing others has also healed himself, and vice versa. One shouldn’t overstate his so-called bubble – it’s really just a chilled, pleasant lifestyle – but it surely promotes peace of mind, and dispels the bad memories.

“I just do the music,” shrugs Boris. “And I don’t think too much. Just want to make the music – to make me happy, to make the people happy…” He turns to check something on Zoom and the patch of skin – what he jokingly calls his ‘tattoo’ – flashes briefly, a hyperlink to a long-ago tragedy.

Click here to change your cookie preferences