Animal Farm at 80: Orwell’s diachronic warning on truth and power

By Euripides L Evriviades

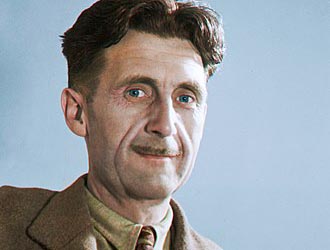

On August 17, 1945, in a London scarred by war, Eric Arthur Blair – better known by his pseudonym George Orwell – published Animal Farm. Eighty years on, it reads less like a fable of its time and more like a permanent warning.

Together with other seminal works like: 1984, Down and Out in Paris and London, Homage to Catalonia, Politics and the English Language and Shooting an Elephant, Orwell shaped the political consciousness of millions, teaching that the greatest battles are not only fought on fields of war but in the manipulation of truth, memory and hope.

At its core, Animal Farm is not just a satire of Stalinism. It is a universal allegory of how revolutions are betrayed, how noble ideals are hijacked by those who crave power, and how language becomes a weapon more potent than any gun. With a single sentence – “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” – Orwell captured the cynical logic of totalitarianism and authoritarianism, past, present and future.

Orwell began writing Animal Farm in 1943, during the darkest years of war. Food was rationed. Paper was scarce. Britain’s alliance with the Soviet Union made criticism of Stalinism unwelcome. Several publishers rejected the manuscript before Secker & Warburg brought it out in August 1945.

From the start, Animal Farm stood apart. In fewer than 30,000 words, Orwell combined simplicity with devastating force. The book has since sold over 11 million copies, has been translated into more than 70 languages and never gone out of print. Across decades, it has been smuggled into censored societies, quoted in protest movements and adapted for stage and screen.

Eighty years on, Animal Farm still resonates. On the farm, truth is never fixed. Commandments change. Slogans are simplified. History is rewritten.

Today, in the age of disinformation, deepfakes, algorithmic echo chambers and AI-driven propaganda, Orwell’s warning about the fragility of truth is more urgent than ever. The war in Ukraine has shown how propaganda, distortion and denial can become weapons of war as powerful as missiles. We see it also in Gaza and other conflicts, where competing narratives fight and kill for dominance.

Too often, we simply do not know where the truth lies. And this uncertainty is corrosive. It erodes trust – including in institutions – undermines democracy and makes diplomacy ever more precarious. This problem will only intensify in the years ahead, on an industrial scale, with repercussions we have yet to fully comprehend.

The animals in Animal Farm rise against their human masters in the name of freedom, only to fall under a new tyranny. History is rife with revolutions that devoured their own children, like the mythical Kronos: the French Revolution, which descended from liberty into terror; the Russian Revolution, which promised equality but led to the Gulags; the dashed hopes of the Arab Spring, where initial euphoria gave way to repression. The cycle is familiar: idealism followed by betrayal; hope consumed by tyranny.

Language is corrupted. “Four legs good, two legs bad” becomes “Four legs good, two legs better.” Words bend until they mean their opposite. Today, slogans, spin and euphemisms too often replace authentic substance: in politics, diplomacy and media alike. Orwell gave us the vocabulary for this: double-talk and double-think. Both remain fixtures of our time, where leaders say one thing while doing another, and where contradictory ideas are made to coexist in the public mind through repetition, manipulation and the constant barrage of media noise. An orchestration of confusion by design.

But Orwell also warned that corruption of words leads directly to corruption of history. As he wrote in 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” That insight could not be more relevant in our time, when history is rewritten, archives manipulated and facts themselves subject to imposed amnesia.

This is why Animal Farm and 1984 must be read together. One dramatises the betrayal of revolutions; the other exposes the machinery of total control: surveillance, censorship, the obliteration of truth itself. Together, they form Orwell’s twin beacons: warnings about how freedom can be lost, both through the betrayal of ideals and through the erasure of reality.

At the heart of that erasure lies the assault on the simplest truths. As Winston Smith in 1984 reminds us: “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.” When regimes dare to deny even that – when they proclaim that 2+2=5 and demand belief, they cross the Rubicon. It is not just the manipulation of facts, but the evisceration of reality itself. Once truth can be bent at will, nothing is safe: law, justice, democracy, diplomacy, even conscience.

Orwell understood why this happens: politics begins with language. The way we speak is inseparable from the way we think. In Politics and the English Language, he argued that political language is designed “to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” That essay remains a must-read – and a must-reread – for anyone who wants to understand both the past and the politics of today.

After four decades in diplomacy, I have experienced how narratives can shape realities. In international relations, perception often outweighs fact. What is defined as real becomes real in its consequences. A lie – or a half-truth which is also a lie – repeated with confidence does not merely circulate; it takes root. And once embedded, it drives policy, fuels conflict and distorts history. Orwell reminds us that vigilance is not optional. It is the price of freedom and democracy.

Orwell’s work also teaches humility. Revolutions – political, technological, even cultural – carry within them the seeds of disappointment. The answer is not resignation but resistance through thought: questioning authority, exposing manipulation, defending truth.

As Orwell put it, “Freedom is the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” That right is not secondary. It is the foundation of all others.

His genius lay not in complexity but in clarity. His prose was plain. His moral vision uncompromising. He insisted that political language should be “clear like a window pane.” In an age of deliberate obfuscation, spin, fog and cacophony, that clarity is no less than an act of resistance.

His slogans from 1984 – “War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength” – were not simply dystopian satire. They were a diagnosis of how totalitarian logic works. These slogans still echo today.

Eighty years on, Animal Farm remains horribly relevant. It shows us that freedom and democracy can be lost not only through violence but through the slow erosion of truth. It warns that ideals and values, if not defended, can be twisted into instruments of control.

Orwell gave us not just books, but tools and a mirror. He gave us diachronic classics: timelessly relevant, true paradigms of political literature. What we see in them depends on us. And what we choose to do with them will decide whether truth, freedom and democracy endure.

Euripides L Evriviades is a former Cypriot high commissioner to the UK and former ambassador to the US. He is now a senior fellow, Cyprus Centre for European and International Affairs, University of Nicosia.

Click here to change your cookie preferences