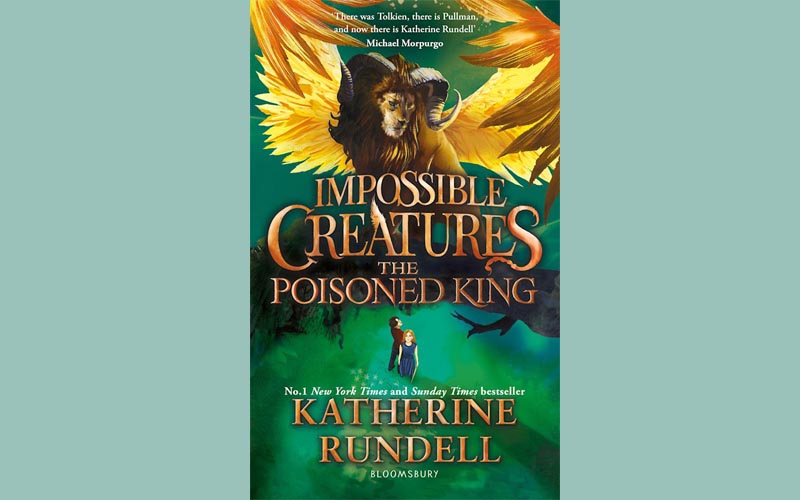

The Poisoned King by Katherine Rundell

People don’t read Charles Lamb enough anymore, which is a terrible shame because he is utterly brilliant in so many ways. Perhaps above all, though, we should read him because of his faith in the power of the child within all of us: ‘Is childhood dead? Or is there not in the bosom of the wisest and the best some of the child’s heart left, to respond to its earliest enchantments?’ Thankfully, in a time where a Lamb revival seems unlikely, we have Katherine Rundell who not only believes that ‘If we were to see our own world and our own creatures afresh, we would find them as extraordinary as unicorns and dragons’, but is able to write books in which a fictional ‘last surviving magical place’ shows us both the necessity and the glory of finding the child’s heart within us, because it is this part of our humanity that provides the possible antidote to a blind and cynical world in which what is needed is ‘more iron-willed cherishing, and more active, political, furious cherishing, because what we have is so beautiful’.

The Poisoned King is the story of two children called upon to save the Glimouria Archipelago, the aforementioned ‘last surviving magical place’, from the cruelty and greed of a very human villain. Christopher Forrester, hero of the first instalment of Rundell’s Impossible Creatures series, wakes one day ‘to find a dragon chewing on his face’ and hear the news that the dragons of the Archipelago are mysteriously dying. Meanwhile, on the island of Dousha, a king is being poisoned and his eldest son accused of the murder. Anya Argen, the accused’s only daughter, knows her father is innocent, and sets out to both prove it and wreak vengeance upon the man who would destroy her world for power.

As Christopher’s and Anya’s quests intertwine and prove to be one, Rundell takes us on a journey that is compelling as much because of her fast-moving plot, her cast of miraculous and deeply resonant characters, and her often lambent prose. With the help of a Sphinx, a Jaculus, a Harpy, a Chimaera, and lots of Gaganas (don’t worry; there’s a bestiary at the end of the novel to help you out), the children find the antidote not just for the literal poison spreading through the Archipelago, but also for the more urgently destructive venom that is human egotism and corrupted desire.

This is an utterly superb book. It is funny; it is profound; it is fun; it is moving. And when Anya Argen declares, ‘You killed me… But I refused to die’, she speaks not just for herself, but for the power of every reader to revive the heart of childhood inside them and respond to the enchantment that surrounds us in our world all the time. Nothing could be worth cherishing more.

Click here to change your cookie preferences