The day after Iran: power, strategy and the unanswered question

Once again, the debate over Iran is framed as a stark choice between strength and weakness, action and inaction. Between good and evil. This is a false binary. The real question is not whether the US can use military force against Iran, but what problem such force is meant to solve, at what cost, and – more importantly – what unintended consequences may follow, regionally and globally.

Military power is a tool. It is not a strategy. When force becomes a substitute for political clarity of purpose, it creates the illusion of decisiveness while storing up strategic failure. The first question, therefore, must be simple and explicit: what is the objective? Ending Iran’s nuclear ambitions? Restoring credible deterrence? Constraining ballistic missiles? Changing regional behaviour? Ending support for non-state actors? Regime change? Or all of the above? History is unambiguous. Wars launched without a clearly defined end state rarely end on favourable terms.

The current crisis is marked by intense signalling rather than open conflict. A substantial US military deployment is accompanied by public warnings and parallel references to a possible deal with Tehran. Against this backdrop, Iran has engaged in indirect talks while insisting that any engagement be conducted on what it calls equal terms – confined to a narrow nuclear agenda rather than the broader security concerns raised by Washington. At the same time, Tehran continues military exercises and warnings of retaliation and wider escalation. Recent incidents, including the US shooting down of an Iranian drone approaching a carrier group, underscore how tightly military signalling and escalation are now intertwined.

Coercive diplomacy

Washington is engaging in classic coercive diplomacy: pressure designed to compel concessions without crossing the threshold into war. It is not stable, but neither is it accidental. As Sun Tzu observed, “the supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.” The danger, however, lies not in signalling itself, but in miscalculation, i.e., misreading intent, overestimating control of events, or underestimating escalation.

This posture is consistent with the US National Security Strategy (NSS) issued by President Trump in November 2025. Hard lessons have been drawn from Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. The NSS moves away from regime change as a declared objective, prioritising national interest, stability and restraint over externally imposed political transformation.

Endless wars, large-scale occupations and open-ended nation-building are no longer viewed as viable instruments of US statecraft – as the recent US surgical military intervention in Venezuela has illustrated. Instead, emphasis has shifted toward sanctions, diplomatic isolation, hybrid tools and economic pressure – all backed by credible military deterrence. Force is not removed from the table, but it is no longer presumed to be the default answer. Any intervention must demonstrate a clear strategic objective, proportional means and a credible political end state.

All politics are local

Foreign policy does not operate in a vacuum. As the late US Speaker Tip O’Neill famously observed, all politics is local. This truism remains valid even in moments of international crisis. With midterm elections approaching, domestic considerations shape decision-making in Washington. Voters are weary of distant wars with unclear purpose. Markets react sharply to instability. Energy prices, investor confidence, and economic sentiment matter. Strength plays well in domestic politics. Open-ended wars do not. This helps explain the tension between rhetoric and restraint that characterises the present moment.

The regional paradox

As I have argued elsewhere the confrontation involving Iran, Israel and the US is not episodic but systemic. It is part of a deeper strategic recomposition of the Middle East – including the Gulf – in which old diplomatic frameworks are eroding and deterrence increasingly substitutes for diplomacy.

Regional actors face a dilemma rarely acknowledged in public debate. Many want Iran contained, deterred and constrained. Some advocate outright regime change. But few want Iran shattered. Saudi Arabia’s recalibration reflects this tension. Public calls for restraint coexist with private warnings that inaction could embolden Tehran. Israel’s posture is similarly layered. Its core objectives remain unchanged, but current restraint reflects tactical judgement rather than strategic retreat. Timing and risk matter.

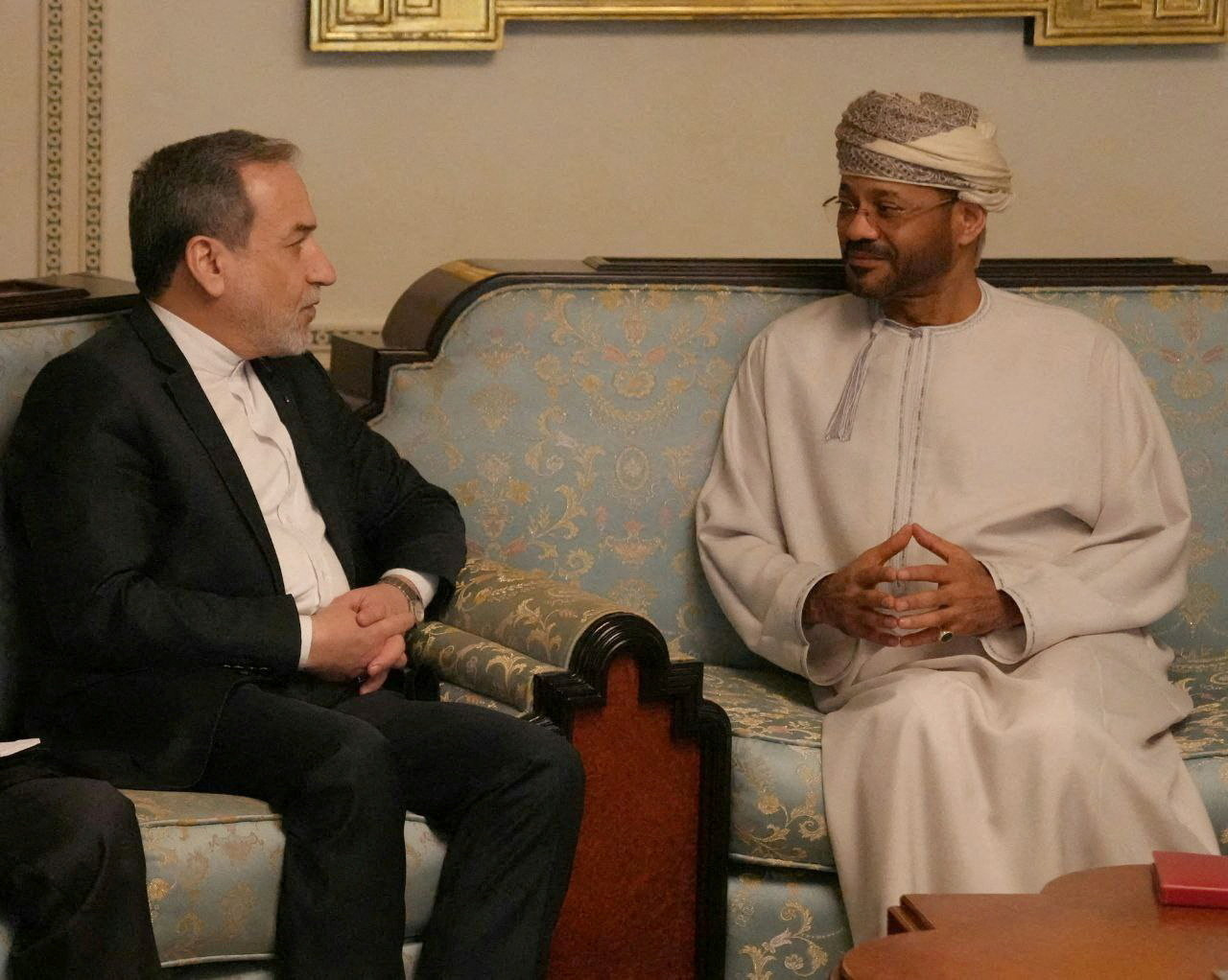

At the same time, regional diplomacy is also in motion. Oman hosted a first round of indirect US-Iran talks on February 6 – a shift from Istanbul that Tehran insisted upon, following earlier facilitation efforts by Turkey, Qatar, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and others. Washington and Tehran signalled a willingness to continue engagement.

The fact that indirect talks have taken place does not mean that Washington has accepted a nuclear-only frame. On the contrary, the core divergence over ballistic missiles, regional behaviour and support for non-state actors remains unresolved – a point the US underlined by announcing fresh oil and petrochemical sanctions within hours of the talks’ conclusion. What this underscores is that even at moments of acute tension, diplomatic channels remain active. Deterrence and dialogue now operate in parallel, often uneasily.

The paradox is simple. A triumphant Iran is dangerous. A chaotic Iran may be worse. Fragmentation, proxy escalation and uncontrollable retaliation would place the region on permanent edge. Stability and predictability – not victory – remain the unspoken regional demand.

The EU’s quiet alarm

The EU watches the crisis with particular unease – and Cyprus feels it immediately. Any major conflict involving Iran would produce direct consequences: energy, trade and financial disruptions, migration flows and renewed instability across the Mediterranean and the Levant, affecting economic stability, security planning and regional credibility in real time. At a time when the EU is already stretched by the war in Ukraine, the demands of defence rearmament, and an increasingly unpredictable US decision-making environment, a Middle East war would not be a distant theatre. It would be felt quickly and directly.

This explains Europe’s emphasis on de-escalation and diplomacy. It is not naïveté. It is vulnerability. It is strategic prudence.

Russia, China and nuclear proliferation

The growing coordination between Iran, Russia and China adds another layer of complexity. Joint military exercises scheduled among Iran, Russia and China, together with political signalling, do not amount to a formal alliance. Moscow and Beijing are unlikely to fight for Tehran, but they benefit from Western distraction and strategic overload.

Escalation hardens blocs, narrows diplomatic space, and accelerates the fragmentation of an already strained international order. A wider conflict would therefore serve interests well beyond the region – and not those of stability. One likely global consequence, particularly if a US strike on Iran coincides with the protracted war in Ukraine, is the erosion – if not collapse – of the remaining institutional constraints on nuclear proliferation. The expiration on February 5, 2026 of the New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) between the US and Russia, leaving the two largest nuclear arsenals without binding limits, underscores how fragile those constraints have become.

The deterrence lesson drawn by many actors is stark. Iran was struck during the 12-day war last June precisely because it did not yet possess nuclear weapons; nuclear-armed states such as North Korea are not. For Iran, and for other astute observers, this reinforces a dangerous but rational conclusion: that nuclear capability, not compliance, is the ultimate guarantor against intervention. That lesson, once absorbed, does not remain confined to one case. It spreads – and with it, the logic of proliferation.

The unanswered question: the day after

The most conspicuously unanswered question is the day after an attack on Iran. What follows a strike? What replaces the current order if it collapses? Regime change is a slogan, not a plan. Nuclear knowledge cannot be bombed away. Proxy networks do not disappear with command centres. Fragmentation creates vacuums that history shows are quickly filled, rarely benignly.

The danger, therefore, is not simply escalation, but consequence without ownership. When the political end state is undefined, force risks becoming an act of demonstration rather than an instrument of strategy. In diplomacy, there is rarely a final full stop. Only pauses, recalibrations, and the continuing necessity to shape an agreement both sides can own – the only kind capable of outlasting escalation.

Click here to change your cookie preferences